With creative artworks that take onlookers to a different world, the ‘Being Borrowed: On Egyptian Migration to the Gulf’ exhibition embodies the life style of the hundreds of thousands of Egyptians who travelled to Arab Gulf states for work during the 1980s and 1990s.

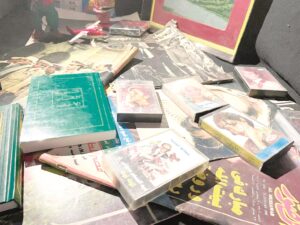

The exhibition showcases a large number of photos of Egyptians’ homes outside Egypt. It also contains photo albums, postal messages that pulsate with stories, and some interactive games visitors can play. The exhibition also contains cassette tapes containing recordings family members sent to relatives outside Egypt during this period or received from them.

The ‘Being Borrowed’ exhibition produces visual anthropological knowledge of temporary migration as an experience.

The various artworks paraded in the exhibition were produced by a workshop on migration through a wide range of topics, such as memories, death, parenthood, belonging and ambition. These artworks were produced through personal narratives.

Egyptians immigrated to Arab Gulf states in their hundreds of thousands with the oil boom at the beginning of the 1970s. However, these travels have had deep impacts on the Egyptian society as a whole, on Egyptian culture and arts.

The ‘Being Borrowed’ throws light on these impacts and brings them to the knowledge of new generations of Egyptians.

The exhibition is held at the Contemporary Image Centre in downtown Cairo.

Exhibition organiser, Farah Halaba, has been painfully impacted by the immigration of Egyptian professionals and workers to Arab Gulf states.

Her father was one of the hundreds of thousands of Egyptians who travelled to the Gulf.

“He continues to be there,” she told the Egyptian Mail.

Sorry to say, like hundreds of thousands of other Egyptians, Halaba’s father cannot afford returning home, due to the tonnes of financial obligations he has on his shoulders.

“Nevertheless, Egyptians’ stay in the Gulf must come to an end one day,” Halaba said. “This is a temporary presence after all.”

Halaba lived in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for 18 years with her father and other family members. In this, she is similar to all the artists who brought their works to the exhibition.

“I have a lot to share and remember from this experience,” Halaba said.

Despite these rich memories, she – like all other Egyptians with relatives working in other countries – worries about the present and the future, especially about the tough times their relatives have to go through and their feelings of loneliness, while they live thousands of miles away from their families and home country.

These worries cause Halaba and other artists participating in the exhibition to see the immigration of their relatives in the context of a border experience, one that leaves its marks on their lives.

Twenty artists are bringing their works to the ‘Being Borrowed’ exhibition which will last until the end of October.

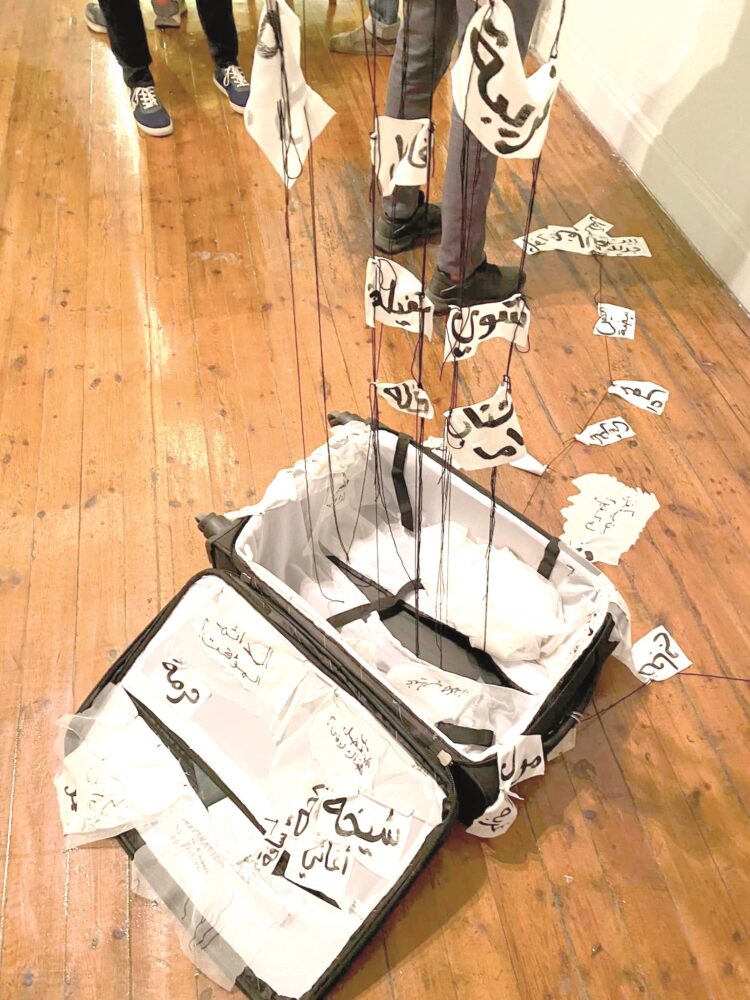

These people opened their travel bags, got their memories and secrets out and are parading them in this museum.

The core idea of immigration to the Gulf, these artists say, is that it creates a temporary life, regardless of the number of years one spends there.

Egyptian workers travelling to the Gulf and their family members who have to accompany them are usually deprived of the stable life other Egyptians enjoy, and have to postpone the establishment of a permanent home.

These travels and the resultant instability fill these people with indelible memories, ones manifest in the different sections of the exhibition. They throb with personal feelings.

Aya Bendary, one of the artists participating in the exhibition, brings to it a travel bag that she keeps open. Overflowing from the bag are fabrics printed in different colours.

Written on the fabrics are also different words that sum up Bendary’s travel experience: ‘travel’, ‘alienation’, ‘Kaaba’, ‘Umra’.

Bendary said the bag is more than just a container for carrying things during travel.

It is rather, she said, a container of actions, plans and hopes, some of them have never materialised.

In the next room, Doha Abulezz, another participant, brought a bundle full of things, including her memories.

The objects Abulezz brought to the exhibition also included the classic game Autobus Complete, which is popular among school pupils.

She said the version of the game she brought to the exhibition recognises only words that are associated with the Gulf.

Game rounds, she added, can only be won by children who are familiar with different place in the Gulf.

In a way, Abulezz’s game explores the notion of identity through language, even as it raises questions about whether by knowing the places recognised by the game migrant children feel natives of the countries where they live.

Lina el-Shamy, a third participant, brought with her archival photographs of furniture in migrants’ homes.

Migrant workers usually have two residences: a temporary one in their countries’ of work and a permanent one in their home countries.

Nonetheless, they never know whether they will ever use this permanent residence.

El-Shamy’s photos show the furniture in migrants’ homes in their countries of work to be light, mostly made of plastic and bare.

This contrasts the furniture in their permanent residences in their home countries, which is usually heavy, mostly made of wood and decorated.

There are beautiful salons in the permanent residences, whereas the ones in the countries of work are full of cardboard boxes where the migrant workers keep different types of things.

“The objects in houses in the countries of work throw light on migrants’ plans to stay temporarily, whereas those in the home countries reflect hopes for settlement and stability in the future, which are sometimes never fulfilled,” she said.

Discussion about this post