In 1928, Egyptologist Mahmoud Hamza (1890-1976) carried out excavations in the vicinity of what is now known as the Qantir, nine kilometres north of Faqous in Sharqiya. He found several artefacts dating back to the reign of Ramesses I (1295-1242 BC) and his successors.

Hamza suggested this was the site of Pi-Ramesses, thought to be the king’s residence during the 19th and 20th dynasties.

A year later, he presented his hypothesis for the first time in Berlin, but his European colleagues were not convinced.

In 1930, he published the results of his research in the Annales du service des antiquités de l’Égypte (ASAE) journal.

A decade later, Egyptologist Labib Habachi (1906-1984) provided evidence to support Hamza’s hypothesis. He had begun work at Qantir and continued the Hamza’s excavations in two villages adjacent to Qantir — Tell el-Dab’a and el Khat’ana.

In 1980, a team from Germany’s Romer and Pelizaeus Museum Hildesheim led by Edgar Push as field director and Arne Eggebrecht took over work on the site. Currently, the project is being led by Egyptologists from Berlin (Alexandra Verbovsek), Bologna (Henning Franzmeier), and Hildesheim (Regine Schulz) in close collaboration with representatives of the Egyptian Ministry Tourism and Antiquities.

To highlight the importance of this city, the Egyptian Museum in Cairo is holding a temporary exhibition titled ‘Antiquities of Qantir: A Century of Excavations and Researches at the Ramesside Residence’.

Around 250 artefacts, of which all were found at Qantir, are on display.

Politics played a major role in the city of Qantir/Pi-Ramesses. The king resided there surrounded by high-ranking government officials.

Pi-Ramesses was the seat of many important institutions, in particular the military and diplomatic. Ancient Egyptian texts indicate that the city functioned as a garrison, a fact that has been confirmed by the discovery of the city’s stables.

Moreover, the location of Pi-Ramesses is strategic, situated on an island on the easternmost branch of the Nile, which offered it protection.

In the city of Pi-Ramesses, a number of palaces are also to be found. It is there that significant historical events, including the famous peace treaty negotiations between Egypt and the Hittites, took place.

Qantir was not only the political but also the religious centre of Egypt in the time of Ramesses II. The most important traditional deity of the region was Seth, whose main temple had been found in Avaris in Sharqia some centuries before.

With the founding of the new residence, the complex was incorporated into the area of the city. A special feature of Pi-Ramesses was the cult worship of statues depicting Ramesses II as a deified king.

On display a limestone stela of Ramesses II depicts him executing one of his royal duties: keeping up order in the world by going to war in foreign countries, holding captives, and presenting them to deities to show that he is fulfilling his role rightfully.

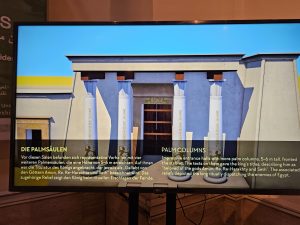

New temples were also built in the city. These were dedicated not only to well known Egyptian gods, such as Amun-Re-Harakhte, but also to foreign deities. In texts, the temple of the Near Eastern goddess of love Astarte is referred to as one of the four main sanctuaries of the city. Two more were probably built for the gods Reshef and Baal, who originate from the nearby Levant.

The city of Ramesses is famous for the large stables that were unearthed there in the 1990’s. They give a vivid impression of how the horses of the royal army were cared for and their myriad purposes.

Coloured images on lintels show horses in front of the name of Ramesses Il highlighting the significance and status that these horses had for the king. The remains of exotic animals that are not native to Egypt, such as giraffes and elephants, were also found. It was first assumed that there had been a zoo within the city, but recent studies suggest that the skulls and skins of these animals were often hunting trophies.

In Qantir/ Pi-Ramesses, weapons for war and hunting were produced in large quantities. Among the objects found are arrowheads and harpoon tips. They are very elaborate such as the arrowheads with articulated wings, or the harpoon tip with the remains of a royal cartouche. Mostly bronze and also slint, chalcedony, or bones were used.

A number of ancient Egyptian texts indicate that the people of Pi-Ramesses lived a prosperous life thanks to their distinguished local produce, such as meat, fish, grain, and wine.

The stone door jambs also indicate the presence of enormous and magnificent villas in the city reaching 1200 square metres in size. Similar to other cities in the ancient world, the city was populated by both wealthy and poorer people.

Aquatic landscapes often adorned palaces in Ancient Egypt. Common motifs are lotus flowers, other water plants, and fish. On display a rarer occurrence is the swimming lady, made of glazed faience.

Also on display are glazed-faience tiles with representations of foreigners, these fragments show parts of images of the traditional enemies of ancient Egypt, such as the Nubians in the south, the Libyans in the west and the Asians in the northeast.

State-of-the-art technologies were used for Pi-Ramesses project from the very beginning. In the 1980’s, databases were already in use, while magnetic measurements followed shortly thereafter.

In addition, new methods were and continue to be used to analyse the findings. Portable X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy devices helped determine the composition of metal objects and thus the sources of copper used in the workshops of Pi-Ramesses. One of the surprising results was evidence for the presence of Omani copper in Egypt.

The exhibition provides an opportunity to visitors to see the virtual rebuilding of Pi-Ramesses. It is being held in Hall No. 44 on the ground floor of the Egyptian Museum. It will run until October 16.

Discussion about this post