Around 225 years ago this month, a momentous event that captivated historians and archaeologists for the following centuries took place.

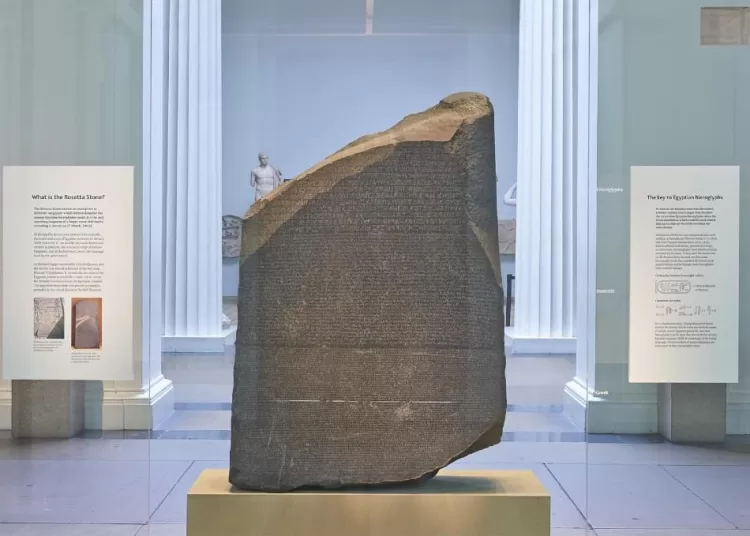

The Rosetta Stone, a striking slab of dark granodiorite, was unearthed, revealing inscriptions in three distinct scripts – the mysterious hieroglyphics, the flowing Demotic, and the familiar Greek.

This discovery was like a key to unlocking the secrets of an ancient civilisation.

The Rosetta Stone’s unveiling marked a turning point in humanity’s understanding of history, shining light on a past shrouded in mystery and intrigue.

Discovered in Rosetta near the Mediterranean coast on a tributary of the Nile during Napoleon Bonaparte’s expedition in Egypt by French soldiers, the inscribed stone fragment caught the eye of officer-cum-engineer Pierre François Xavier Bouchard (1772–1832), amid the construction of fortifications.

Recognising the significance of the adjacent Greek and hieroglyphic writings, Bouchard foresaw that each script held a version of the same text.

This premonition was validated when the Greek portion detailed the decree to inscribe the text in sacred (hieroglyphic), native (Demotic), and Greek characters. Thus, the Rosetta Stone, or “la Pierre de Rosette” in French, got its name from the city of its discovery.

Over the centuries, since its discovery, the Rosetta Stone has emerged as a global symbol, embraced by various factions.

Housed presently in the British Museum, its presence there stands as a relic of France and England’s imperial pursuits during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The stone still bears engravings recounting its capture by the British Army in 1801 and its presentation by King George III.

Egypt found itself situated amidst power struggles during this period, being part of the Ottoman Empire.

The invasion by Napoleon in 1798, followed by the defeat inflicted by British and Ottoman forces in 1801, plunged Egypt into an era marked by exploitation.

The stone was officially ceded to the British through the Treaty of Alexandria in 1801 and then made its way to the British Museum in 1802, where it has been a prominent exhibit ever since.

Many people argue that the removal of the Rosetta Stone constitutes a colonial act of “theft” and advocate for its return to Egypt as a means of addressing historical injustices.

Renowned Egyptologist Zahi Hawass has been actively involved in efforts to repatriate stolen artefacts back to Egypt since 2002.

His focus is on returning recently looted items, rather than legitimately acquired Egyptian pieces currently held in various museums worldwide.

He made a petition to repatriate the Rosetta Stone from the British Museum and the Zodiac of Dendera From the Louvre back to Egypt.

“Before the founding of the antiquities service in the 19th century, while Egypt was under the control of the French and the British, the country was plundered and its antiquities were illegally exported,” Hawass wrote on his social media platforms.

“As a first step towards the decolonisation of foreign museums, we are requesting the return of two of the iconic objects that were pillaged from Egypt: the Rosetta Stone at the British Museum and the Zodiac of Dendera at the Louvre,” he added.

He noted that these artefacts were taken during colonial times and should be returned to their rightful home in Egypt.

“By returning these objects, Western museums can show a commitment to decolonisation and reparations,” Hawass wrote.

“The artefacts would be displayed in the upcoming Grand Egyptian Museum,” he added.

He said his petition calls on the international community to support the repatriation of these items.

The pivotal role of the Rosetta Stone in decoding ancient Egyptian scripts has popularised the term “Rosetta Stone” to denote anything that deciphers codes or uncovers hidden enigmas.

This widespread recognition has been embraced by the business world, notably exemplified by the successful language-learning software named after it.

In contemporary global culture, “Rosetta Stone” has become a ubiquitous term, potentially leading future generations to use it without grasping its origins in the fortuitous discovery of a distinctive rock in Egypt.

Scholars’ earnest endeavours to crack the Egyptian scripts, aided by the Greek translation, triggered a frenzy of decipherment in Europe thanks to the trilingual inscription on the Rosetta Stone.

While the stone is often associated with Egyptian hieroglyphic script, the initial breakthroughs in decipherment concentrated on the demotic script as it was the most well-preserved of the Egyptian variations.

French philologist Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy(1758–1838) and his Swedish pupil Johan David Åkerblad (1763–1819) successfully deduced the phonetic values of numerous alphabetic signs, interpreted personal names, and translated a handful of other terms.

Their approach began with matching the sounds of the personal names of the monarchs in the Greek text with characters in the Egyptian renderings.

These advancements laid the groundwork for the famed competition between Thomas Young (1773–1829) and Jean-François Champollion (1790–1832) to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Both men exhibited brilliance, with Young making substantial progress in deciphering both hieroglyphic and demotic scripts, but Champollion ultimately achieved the breakthrough.

The Rosetta Stone’s text, known from the Greek version, contained a decree issued in the name of King Ptolemy V Epiphanes.

In 196 BC, a synod of priests from various regions of Egypt gathered to commemorate the coronation of Ptolemy V Epiphanes, which had taken place the day before in Memphis, the historic capital of Egypt.

Despite Alexandria’s economic supremacy at the time, Memphis maintained its significance as a symbolic tie to Egypt’s pharaonic history.

The decree opens by chronicling the king’s laudable deeds and accomplishments, such as generous temple offerings, tax reductions, and the restoration of peace in the aftermath of a revolt that began during the reign of his predecessor, Ptolemy IV Philopator.

In appreciation of Ptolemy V Epiphanes’ substantial contributions to Egypt, the council of priests pledges a series of endeavours to uphold his royal legacy.

These initiatives involve the creation of new statues, enhancement of his sanctuaries, and the organisation of festivities to honour his birthday and accession to the throne.

Lastly, the decree dictates that it be inscribed in hieroglyphics, demotic script, and Greek on stone steles to be placed in temples throughout Egypt.

Discussion about this post