Many years ago this paper carried a poetry corner.

By way of relief from the doom-and-gloom headlines, let’s have a love poem. “My love is like a red, red rose./She strikes a wonderful pose/When she holds a hose/To water down the landing outside our flat./For goodness’ sake, stick to prose.” Indeed I shall. Writing real poetry is mind-bogglingly difficult even if all the big names in verse make it look so easy.

Meanwhile, I pity students who will be dragged through English poetry in the coming academic year. Probably one of the most pointless exercises is writing an ‘appreciation’ of a piece of poetry.

You have to say what you liked about the poem and the poet’s use of language and what was in his/her mind at the time. Students are told to like poetry. There is no dislike. It would be wonderful if a pupil wrote: “I hate this poem because it is carp.” Imagine the teacher reading this terse judgment.

“What a strange comparison, Ashraf,” the teacher will say.

“What comparison, sir?”

“You are likening the poem to a species of orange fish.”

“That’s not what I mean, sir. I didn’t spell the last word right.”

Quite.

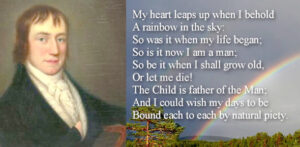

Anyway, Wordsworth’s heart leapt up when he beheld a rainbow without a single rhyme in those few lines. So what? “I am totally indifferent about this poem because I saw a rainbow the other day and my heart didn’t leap up, down, or sideways, or anything.

” Why do bad poets insist on producing drivel that rhymes? As usual, school is responsible for miseducating generations regarding the uses of poetry, about which the book of the same name by the poet T.S. Elliott has been ignored by generations of schoolteachers. Most people develop an awareness of poetry in three stages.

Firstly, as children, they are fed songs and rhymes, which are easy on the memory and sometimes serve a useful purpose, such as “One, two, three, four, five/Once I caught a fish alive…” As for “Georgie Porgie puddin’ an’ pie/Kissed the girls and made them cry”, no one in the teaching profession dare tell their little charges that this was a reference to an early 19th English monarch who was a womaniser when he was Prince of Wales.

Secondly, many of us as adolescents produce mawkish tripe about love, death, depression, the pain of growing up and other cheerful subjects.

Lastly, we persist in the production of sickly garbage, but this time it’s about pollution, global warming, solar cooling, and melting ice in the glass of lemonade on a blisteringly hot afternoon on a planet to which we will have to move if corporations render the planet uninhabitable, and, more to the point, unprofitable.

Let’s have a go: “There ain’t no more coal in them there hills./All we’re left with are tonnes of trash in landfills./Where did all that oil go?/ Through miles of pipeline did it flow./I don’t half miss Cairo, though.” Mm. There’s something there.

Otherwise, most of us never put a rhyme together ever again, especially that one in the previous paragraph.

Unlike prose, poetry is the toughstone of taste. For instance, it takes time for most of us to form a judgment of, say, a novel. Some may put the book down at the end of the first chapter, or the first paragraph. Others will plod on to the end and say: “What a load of rubbish, but it was enjoyable rubbish.” You might flick on a telemovie and decide that it is slow to warm to its theme.

The commercial breaks might be more interesting, or the story and characters ‘grow’ on the viewer. Not so with poetry. Read the first stanza and you should have a clear idea of what to expect. The Robert Burns classic in which he compare his love to a “red, red rose” swiftly takes the reader (or listener) through an account of his feelings. “To be or not to be” sums up an inner conflict from the first line.

“There was a young lady from Bude…” promises a bawdy tale of an attractive bather in a lake and passer-by in a flat-bottomed boat. Whether the lady in question has a flat derriere, the composer of the limerick does not say. But it was not always like that for poetry.

Arabic poetry from the pre-Islamic age and Beowulf, the oldest poem in an early form of English are examples of some of the world’s oldest literature, as are Geoffrey Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales’ and the French ‘chansons de geste’. In an age when most people were illiterate, stories in poetic form were easy to commit to memory than prose and transmit from one generation to the next.

By the way, you will not find a single rhyme in Old English poetry, but you will find plenty of alliteration, as shown by this line with all the f-sounds from the prologue to Shakespeare’s ‘Romeo and Juliet’: From forth the fatal loins of these foes…” Nor does Latin poetry rhyme.

Ending lines with words containing similar vowels and diphthongs originated in French poetry. Why the English adopted this convention defies reason because the English language is reputed to be poor in rhymes. But what about words like ‘cat’, ‘mat’, ‘bat’ and many more? Many words in the basic vocabulary of English rhyme, as well as words ending in ‘-tion’ and ‘-ity’.

However, a common error is to allow one’s poetic composition be dictated by rhyme, and not vice-versa, hence absurdities like: “The big brown cat/Played with a rat/On a woollen mat?/Which is a pity/Because the bat/That flew in from the city/Came in anticipation/Of feline discussions about the state of the nation.”

Unless you want to produce nonsense and emulate Edward Lear (not to be confused with ‘King’), let rhyme steer you. If you want to celebrate your love for the eternal she, go easy on the rhyme, and shove in a few archaisms and play about with the word-order. “Thou fair’st sight/I ne’er hight/Ugly, for what boot/If thou wert bald as a coot?/Stay! Hark! Go where thou list/And fear not being dissed.”

I said go easy on the rhyme, didn’t I? Now you will need some foot-notes to explain ‘hight’ (call), ‘boot’ (benefit) and ‘list’ (pleases). If you want your listener or reader to snigger, you will succeed with tripe like the above.

To be taken seriously as a poet requires sincerity. By this I mean a passion for the subject of the poem. You want your reader’s ear to be enthralled, not to captivate him or her with your verbal skill that includes contrived rhymes, awkward word order and expressions that would not look out of place in Shakespeare or the waste paper basket.

Wordsworth did not set out to impress, except to make us aware of the intense experience of being alive that is often overshadowed by our drive for “getting and spending” on the latest mobile phone. You might not think a “red, red rose” is a striking comparison to one’s love for another person. Sooner a rose than “my love is like a great big palm tree”.

The boundary between great poetry and doggerel is extremely fine – one false move with a word or a rhyme and it’s snickering all round. So before you hand in your poems about the vicissitudes of everyday life or about urban versus rural living, read Wordsworth’s ‘The world is too much with us’ and a good translation of Ovid’s ‘The town and country mouse’.

Discussion about this post