Slowly, one can look around and begin to imagine the merchants haggling, grooms scurrying to and fro, the camels laden with packages and goods coming in the same gateway, donkeys, boys, dust, noise, laughter, arguments, heat, life in the16th century.

The imposing Wikalet (caravanserai) el-Ghuri is just one of the magnificent complexes of some 500-year-old buildings known as el-Ghuriya in Islamic Cairo, on the right of Al-Azhar street below the pedestrian bridge as you approach Al-Azhar Mosque from downtown Cairo.

If you follow the mosque around from its main entrance and turn right into a bustling street past a fruit and vegetable market you will find the entrance to Wikalet el-Ghuri on your left.

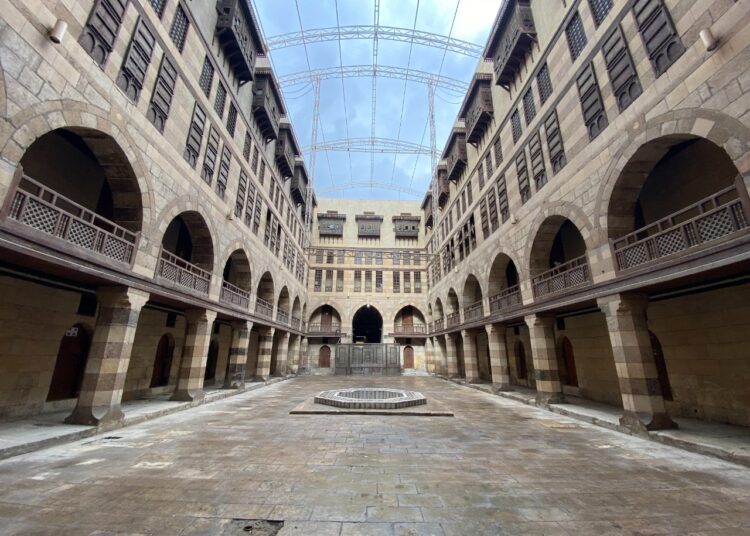

Step down through the high, wide portal into a rectangle of light and tranquillity surrounded by striped arches and mashrabiya latticed windows. You are now standing in one of the few remaining wikalas and the most outstanding extant example of these trading establishments.

“Wikalet El-Ghuri was an establishment hosting the Egyptian traders who came from out of Cairo and foreign traders who hailed from Maghreb, Levant and Central Asia, usually by boat and camel,” Gamal Abdel Rahim, Professor of Archaeology and Islamic Arts at Cairo University, told the Egyptian Mail.

“It served as a marketplace for selling and buying goods and a venue for making trade deals,” he added.

Abdel Rahim said that Al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghuri, the Circassian Mamluk Sultan ruled between 1501-1516, built the wikala along with his mosque, sabil, mausoleum all in 1503.

Circassian Mamluks ruled Egypt for 135 years (1382-1517), with 23 alternating sultans.

The wikala consists of a ground floor and four storeys.

“If we compare it to today’s facilities, it combines a bourse, a shopping mall and a hotel in one structure,” Abdel Rahim said.

The open courtyard in the ground floor is a place where business deals were conducted like today’s stock exchange.

Traders also showcased their goods on that floor. The first and second storeys were used as stores of the goods.

The third and fourth storeys were for traders’ accommodation. They were linked together by inner stairs like a duplex.

The fourth storey has mashrabiyas to provide privacy to the merchants’ wives. At the bottom of these mashrabiyas there are two rows of windows equipped with wooden screens that have movable covers that allow them to look at the courtyard without being seen.

“The wikala played an important role in the Egyptian economy as it brought income to the country. When the traders sold their goods, they also bought Egyptian goods and took them to their countries,” Abdel Rahim said.

He added that merchants in Wikalet El Ghuri specialised in selling cotton and sometimes dates.

He added that the structure still exists thanks to the efforts made by Comité de Conservation des Monuments de l’Art Arabe in restoring it during the time of Khedive Abbas Helmi, last Khedive of Egypt (1892-1914).

Established in 1881, the Comité was responsible for preserving Islamic and Coptic monuments in Egypt.

In the 1960s, Abdel Rahim added, the Ministry of Culture restored it again and used most of the upper-story rooms, that once stored wares from the East or housed merchants, as studios for plastic artists and handmade artisans to teach young generations about these arts. But the wikala was neglected in the 1990s.

Since October 2005, Wikalet el-Ghuri has become a centre for cultural and architectural lovers in Islamic Cairo through the activities run by the Cultural Development Fund and Fine Arts Sector, both affiliated to the Ministry of Culture.

Wikalet el-Ghuri is located at 3 Mohamed Abdou Street, off Al-Azhar Street, Islamic Cairo. It is open daily from 9am to 4pm.

Discussion about this post