As an ancient site, Saqqara is the scene of a large number of pyramids that emerge from the sand like dragon’s teeth.

Most striking of these landmarks is the famous Step Pyramid.

Built in the 27th century B.C. by Djoser, the Old Kingdom pharaoh who launched the tradition of constructing pyramids as monumental royal tombs, this pyramid is one of over a dozen of others that are scattered along the site.

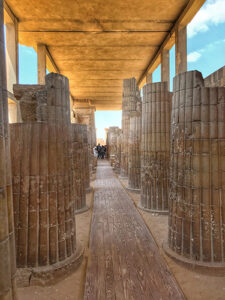

The same site is also dotted with the remains of temples, tombs and walkways that, together, span the entire history of ancient Egypt.

But beneath the ground is far more – a vast and extraordinary netherworld of treasures and one archeological mission after another unearth surprising parts of these treasures.

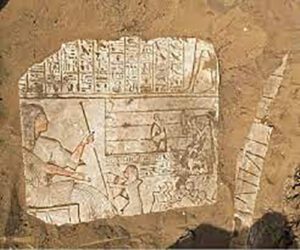

These treasures included in the past years gilded masks, finely carved falcons and painted scarab beetles rolling the sun across the sky.

Archaeologists working in the area discover dozens of expensive coffins jammed together, piled to the ceiling as if in a warehouse.

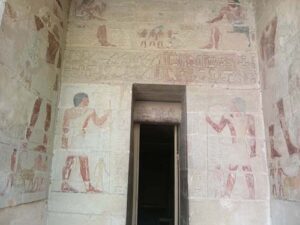

Beautifully painted, human-shaped boxes stacked roughly on top of heavy limestone sarcophagi and gilded coffins packed into niches around the walls.

Saqqara, a sprawling necropolis that once served the nearby Egyptian capital of Memphis, is an open site that continues to give out.

In the past years, archeological missions working in the area uncovered hundreds of coffins, mummies and grave goods, including carved statues and mummified cats, packed into several shafts, all untouched since antiquity.

The troves discovered includes many individual works of art, from the gilded portrait mask of a sixth- or seventh-century B.C. noblewoman to a bronze figure of the god Nefertem inlaid with precious gems. The scale of discoveries has excited archaeologists.

Saqqara was once at the centre of a national revival in pharaonic culture and attracted visitors from across the known world.

The site is full of contradictions, entwining past and future, spirituality and economics.

It was a hive of ritual and magic that arguably could not seem more distant from our modern world.

Yet it nurtured ideas so powerful they still shape our lives today.

Travellers visiting Egypt have long marveled at the vestiges of the pharaohs’ lost world—the great pyramids, ancient temples and mysterious writings carved into stone.

Apart from its eroding pyramids, Saqqara was known, by contrast, for its subterranean caverns.

It did not attract much archaeological attention until the French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette, who became the first director of Egypt’s Antiquities Service, visited in 1850.

He noticed the half-buried statue of a sphinx, and probing further he found a sphinx-lined avenue leading to a temple called the Serapeum.

Beneath the temple were tunnels that held the coffins of Apis bulls, worshiped as incarnations of Ptah and Osiris.

Since then, excavations have revealed a history of burials and cult ceremonies spanning more than 3,000 years, from Egypt’s earliest pharaohs to its dying breaths in the Roman era.

Discussion about this post