“Take a selfie with Ptolemaic queen”, reads a sign beside an 11-metre statue of a queen in the form of the goddess Isis inside the newly reopened Graeco-Roman Museum in Alexandria.

The 25-ton statue is one of many of similar design, but this one is the biggest, said Sobhi Ashour, professor of Graeco-Roman Art and Archaeology at Helwan University.

Ashour added that the Isis statue was found in the 1960s by an Egyptian diver Kamel Abu el-Saadat north of the Qaitbay Citadel in the eastern port of Alexandria.

The statue of the ‘selfie-genic’ queen is not alone. A black basalt statue of one of the Ptolemaic queens is portrayed as Isis. Her robes are carved so skillfully that you can imagine they might billow in a light breeze.

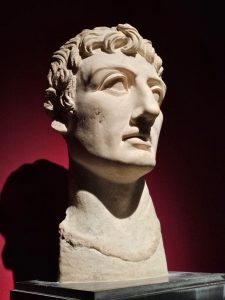

The Graeco-Roman Museum has the only portrait of Cleopatra and that of her father, Ptolemy XII Auletes. This artwork dispels the myth that she was black, negroid, or resembling a Hollywood actress. Cleopatra VII was a Greek, after all, even if she did not look like Elizabeth Taylor in the 1963 film of the same name.

Here Cleopatra VII is represented with delicately modelled facial features and an elaborate hairdo. The circlet on her head, wreathed with cobras, and another rising from her forehead indicate that she is the ruler of Egypt.

Museum director Walaa Abdel Aati was a mine of information on all the displays. Clearly, she is passionate about the Graeco-Roman period. She said that the museum displays heads portraying Alexander the Great made of different materials like pink granite that do not exist in any other museum regarding the numbers or the sizes.

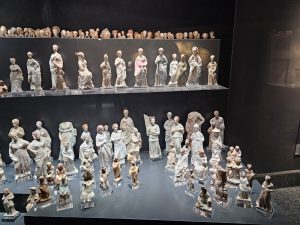

While on the subject of statues, the museum possesses a fine collection of tanagra statuettes in terracotta. Large quantities of these figurines were found in ancient burial sites in Tanagra, which is now the modern-day municipality that lies north of Athens.

These human effigies, whose purpose matched the ancient Egyptians’ concept of the Afterlife, were produced in various attitudes and were intended to represent the life of the deceased.

They were thought to bring comfort to the dead on their way to the next world taking something from their old lives with them. The largest collection of Tanagra figures outside Greece was unearthed in the early Alexandrian cemeteries of Shatby, Hadra and Ibrahimeya.

Of course, the museum would not be complete without the Roman element.

Abdel Aati referred to statues of Roman emperors who visited Egypt: Augustus, founder of the Roman Empire, Marcus Aurelius and Hadrian. The last name is more famous for commissioning the wall between Scotland and England, marking the northernmost limit of the Roman Empire, than his ardent admiration for Greek culture.

Hadrian is believed to have rebuilt the Serapeum in Alexandria. The remains of this temple can be seen today.

This leads us on to the largest wooden statue dating from the Ptolemaic and Roman periods in the museum collection is that of Serapis, a “syncretic Graeco-Egyptian deity” combining aspects of Osiris and Apis. Here he is shown seated and holding what is believed to be a sceptre in his left hand. Traces of black paint are still visible in the eyes as well as splotches of red on his robe.

On display a modern-day simulation of a Roman house recreated with modern materials. The house consists of a banqueting room, with two authentic marble statues of a man and a woman reclining, each holding a drinking cup in their hands as one of the scenes of domestic daily life. There is a library with modern papyrus scrolls.

This private bath belongs to the hip-tube type of baths of Greek origin, which continued in use in Egypt during the Roman era. The bath includes a basin for water purification.

On display the kitchen which includes stoves, large storage vessels and other household utensils. A triangular niche for the placement of oil lamps for lighting is also displayed.

The banqueting room, which was an essential component of Greek and Roman large houses and urban villas, is on display.

In this room, which is located near the entrance, the owner received his male guests and held banquets and gatherings of elites.

In this room, which is located near the entrance, the owner received his male guests and held banquets and gatherings of elites.

For fans of theatre, a statuette of an actor — possibly 4th century BC — wearing a comic mask and a short chiton, a tunic fastened at the shoulder, revealing his pot belly. He is playing the role of a slave taking refuge on an altar to avoid his master’s punishment.

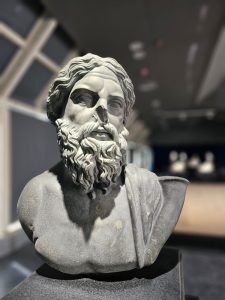

The River Nile is well represented by statuary, notably the elderly man with long hair with a central parting and dressed in a typically Greek mantle, known as a himaton. On his left is an empty cornucopia, perhaps telling us that it is the end of the eating season.

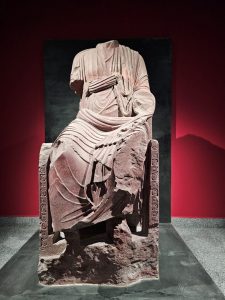

In the section of the museum devoted to the Byzantine period is a headless-statue of Diocletian. One historian commented: “It is perhaps Diocletian’s greatest achievement that he reigned twenty-one years and then abdicated voluntarily, and spent the remaining years of his life in peaceful retirement.” But he was no lover of Christians as he was responsible for the Roman Empire’s largest and bloodiest persecution from 303 to 312 AD. It is just as well the statue has no head.

How did sculptors execute their work so perfectly? The answer is to be found in the museum’s gipsoteca, a plaster cast gallery — the first of its kind in Egypt. Here you will find the ‘sketches’ in terracotta and plaster on which the final works were modelled. In other words, this is how sculptors and their assistants ‘got it right’.

If you are seeking inspiration for a striking floor design in your living room, you can see a mosaic floor that was recovered from a villa in Alexandria. The central panel shows the face of Medusa with snakes instead of a full head of hair. According to Greek mythology, one look from her would turn a mortal into stone. She was killed by Perseus, who used his shield as a mirror to see his victim, which conjures up fantasies on the fate of a cantankerous mother-in-law.

For religious life, a 180-cm basalt statue was probably dedicated to Hadrian or by the emperor himself to Sarapis in the Alexandria temple, during his visit to Egypt in 130 AD. The bull was a sacred symbol of Osiris-Hapi, the god of Memphis, an Egyptian deity since Pharaonic times as a god of the underworld and a symbol of the annual resurrection of nature, and Egyptians and Greeks.

For the afterlife, sarcophagi decorated with garlands (floral wreaths) were common. Garlands were usually carried by mythological figures such as Dionysus and Herakles, both of whom symbolise the victory over death and eternal blessed life.

There are also artefacts shedding light on trade, coins, crafts and industries of the Alexandrian society.

There is also a library, which has 12,000 books in different languages, in addition to a hall for rare books.

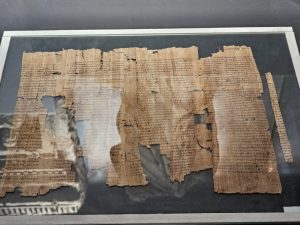

Fed up with all those statues? Maybe you would like to peruse a few lines of Homer’s Iliad, or rather, a scholia based on this compendious work explaining meanings and ironing out errors in previously copied texts. It’s all Greek to most people.

The Graeco-Roman museum was opened by Khedive Abbas Helmy II in 1895 and was added to the list of Islamic and Coptic antiquities in 1983. In 2005, it was closed for refurbishment.

On October 11, Prime Minister Mostafa Madbouli, Minister of Tourism and Antiquities Ahmed Issa and Supreme Council of Antiquities Secretary General Mostafa Waziry reopened the museum.

Among the museum’s 6,000 artefacts are a number of Mycenaean vases and amphorae, which are evidence of trade between Egypt and the Hellenic world that continued until c. 1075 BC.

In 332 BC, an army of Macedonians and Greeks led by Alexander the Great invaded Egypt and defeated the Persian garrison stationed there. The Egyptians hailed as a liberator. Alexander then marched on to Memphis where he was crowned pharaoh and later visited the temple of Amun at Siwa to consult the oracle.

On his way to visit the temple of Siwa, Alexander selected the site of the Egyptian fishermen’s village of Rhacotis where he ordered the foundation of a new capital, Alexandria.

Discussion about this post