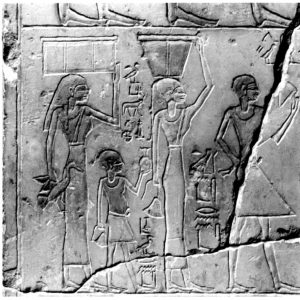

Friezes and inscriptions depicting Asiatic, Libyan and Kushitic women depicted in ancient Egyptian sources show that the ancient Egyptians were aware of other cultures.

Professor Mamdouh Farouk, chief curator of the Imhotep Museum in Saqqara, wrote in his thesis “Foreign Women in the Ancient Egyptian Civilisation – From the First Dynasty (3100 BC-2900 BC) to the end of the New Kingdom (1550 B-1069 BC)”, that foreign women came to Egypt as war captives, slaves, diplomatic delegations, immigrants and political marriages.

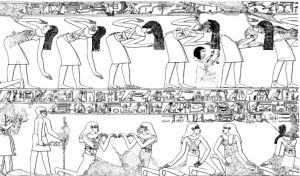

“The Libyan female, in the Old Kingdom (2686 BC-2181 BC), was portrayed on funerary temple walls and causeways built for kings in the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties in recognition of military campaigns and trade relations,” Farouk added.

Thousands of female captives were brought to Egypt as hemet, meaning servant slaves in the middle and new eras.

“They were given as a reward to military leaders by the king. They were also the king’s concubines and maidservants. The rest were sold to the high-ranking officials and the elite of Egyptian society,” Farouk told The Egyptian Gazette.

Foreign males and females were Egyptianised by teaching them the ancient Egyptian language, he said.

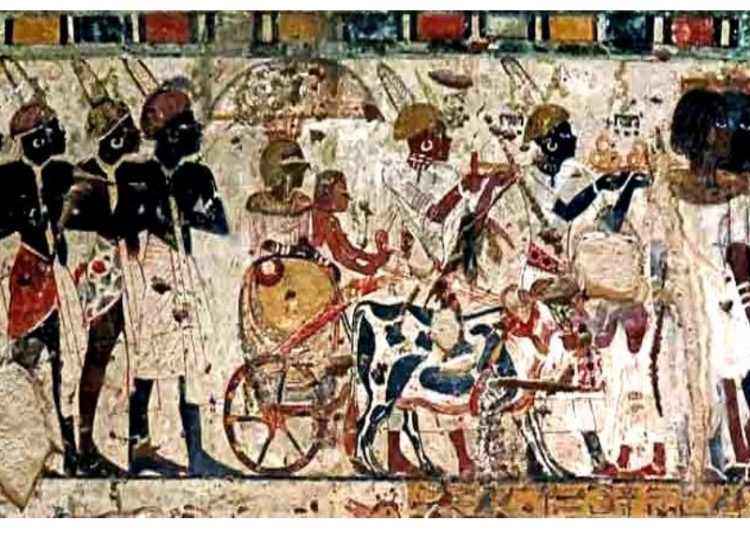

Several scenes record the arrival of multi-ethnic women in diplomatic delegations, who were presented as tributes to the king fulfilling the obligations of loyalty and obedience, or to cement diplomatic relations between the two countries as shown in the tombs of Khnumhotep II in Minya and Rekhmire in Thebes.

Foreign female servants were bequests as property and the fate of foreign children is determined according to the mother’s status, Farouk said.

Inscriptions in Serabit el-Khadem in Sinai shed more light on Asian migration, as in the form of a woman riding a donkey with some men of Retnu race to work in Egypt’s mines and quarries, Farouk added.

“So we find that the beautiful women became concubines and plainer specimens were weavers, ploughwomen, cattle breeders and wheat growers, or as singers and dancers, who sometimes paid for their services.

“Egyptian texts say male and female slaves cleaned temple pools and took part in religious ceremonies.”

Some kings in the New Kingdom held political agreements and treaties with their Asian counterparts.

For example, he said, political intermarriage was a regular practice by Egyptian kings from the 18th dynasty until the end of the 19th dynasty to maintain peace and consolidate political relations, as did as Thutmosis IV, Amenhotep III, Amenhotep IV, Thutmose III, Ramses II and Ramses III.

The first indications come in the Fourth Dynasty since Queen Meresankh III, the wife of King Khafre, may have been of Libyan origin.

The study gives evidence that King Mentuhotep II married Nubian women such as the queens Ashet and Kemsit.

The policy of intermarriage began between the kings of Egypt and the rulers of neighbouring countries, in the 18th dynasty, during the reign of King Thutmosis III, who married three Syrian princesses, and they became part of the king’s harem. They were buried together in the Valley of the Queens.

King Thutmose IV married a Mitannian princess. Amenhotep III followed the policy of his father, Thutmose IV, and married the daughter of a Mitannian King.

The thirty-fourth year of the reign of King Ramses II witnessed the most famous case of political marriage between him and the eldest daughter of the Hittite King Hattusili III, who accompanied his daughter to Egypt to attend her wedding. The event was recorded on stelae, which is found in Abu Simbel, Karnak and Elephantine Island.

Discussion about this post