Egypt buzzes with the resonant echoes of ancient rituals that pay tribute to the life-giving force of the Nile River.

Hapi, the ancient Egyptian god that embodied the annual floods of the Nile River, is at the centre of this show of dedication which started in mid-August.

Hapi was revered as the deity responsible for the yearly overflowing of the Nile.

This natural event brought life-sustaining silt to the river’s shores, enabling bountiful harvests for the Egyptian people.

This deity held significant importance in Egyptian culture and was honoured with titles, such as ‘Lord of the Fish and Birds of the Marshes’ and ‘Lord of the River Bringing Vegetation’.

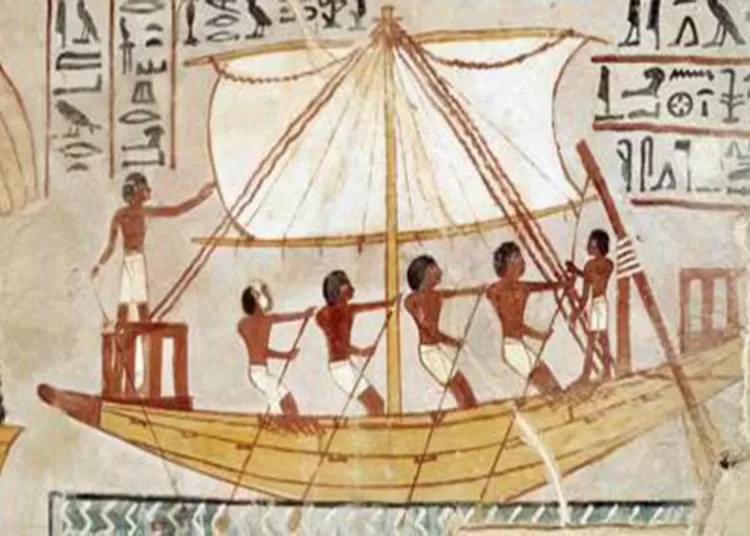

Depicted as a robust man with a strong physique, prominent chest, and large belly, Hapi embodied the nourishing waters that sustained life and prosperity.

It was intricately connected to its creation myths, believed to incorporate the primordial waters from which Egypt’s land arose in the dawn of existence.

At times, the ancient Egyptians likened Hapi to the god Osiris, associating its union with Isis to theannual Nile flood that brings life to Egypt’s fertilelands.

The divine marriage between the two gods bore fruit in the form of Horus, symbolising rebirth and renewal.

The ancient Egyptians observed the Nile’s annual flood as the commencement of the year in their calendar.

This flood typically began in mid-August, rose to its peak in September, and then receded, reaching its lowest levels in May each year.

They meticulously monitored flood heights, using numerous Nilometers (water level measurement tools) positioned along the river.

They determined that a rise of 16 arm lengths signified the optimal flood level, guiding their assessments of crop yields and applicable taxes on the farmland.

The ancient Egyptian religion highlighted the annual rituals before and during the arrival of the flood to ensure a bountiful and continuous inundation of the land.

Originating in the Middle Kingdom era around the 20th century BC, the rituals, known as the ‘Nile Songs’, glorified the river.

On the slopes of the Gebel al-Silsila, north of Aswan, three ancient scenes were uncovered. Inscribed with hieroglyphics, the scenes detailed royal decrees from Pharaohs, Amenhotep I, Ramses II, and Merneptah. They date back to approximately 1300-1225 BC.

These official decrees confirm the annual celebration of the god Hapi in Gebel al-Silsiladuring the peak and lowest points of the flooding season.

The festivities involve various offerings, including animal sacrifices, vegetables, flowers, fruits, and small statues of the deity, to honour the Nile.

The decrees also mentioned the ritual of throwing a book of Hapi, a papyrus scroll listing sacrifices that was either burned on an altar or cast into the river.

The Harris papyrus, dating back to around 1150 BC and now preserved at the British Museum, contained two extensive lists of offerings to Hapi, with a notable mention of a unique practice involving the sacrifice of statues referred to as the images of Hapi, dedicated to the god of the Nile.

Historical records suggest that until the 18th century, the Egyptians used wooden dolls to increase the river’s water levels.

A significant myth revolves around the ancient Egyptians honouring the Nile during the feast of god Hapi by offering a beautifully adorned girl as a sacrificial tribute, casting her into the river.

The girl was married to the god Hapi. One year, when the only remaining girl to be wed was the king’s beautiful daughter, the king was distressed at the thought of her being sacrificed to the Nile.

Fortunately, her quick-thinking maid concealed her and crafted a wooden doll resembling her.

During the event, the maid tossed the doll into the Nile without raising any suspicions.

The legend surrounding the true bride of the Nile is merely a tale mistakenly associated with Egypt.

It is historically known that the religion of the ancient Egyptians strictly prohibited any form of human sacrifice.

Discussion about this post