It was in March of 2011, only two months after the Hosni Mubarak regime fell, following 18 days of street protests, when a Salafist leader met dozens of followers in a mosque in the northern coastal city of Alexandria, a stronghold of the ultraorthodox Salafists, to deliver a lecture on Salafist thought.

This was a promising time for the nation’s Islamists: the secular political parties, including the leftist, liberal and centrist parties, were weak and fragmented.

The Islamists, especially the Muslim Brotherhood and the Salafists, were powerful, united and were ready to rule.

Following the lecture, some of the followers of the sheikh approached him and asked him questions about what the Islamists should do with Egyptian antiquities if they came to power.

The sheikh looked around and then cautiously told his audience that antiquities should be covered with wax.

“No, we should destroy them altogether, sheikh,” one of his listeners retorted.

A referendum on whether to chart a new constitution before holding the parliamentary and presidential elections, was approaching and the Islamists pressed for holding the elections, believing that the polls would bring them into Egypt’s saddle.

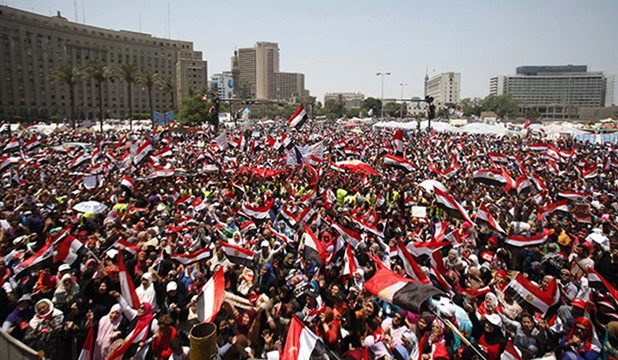

This was not Mediaeval Age Egypt, but Egypt of 2011 which was preparing for Islamist rule, a nightmare that was ended by the June 30 revolution of 2013, which was backed by the Egyptian army.

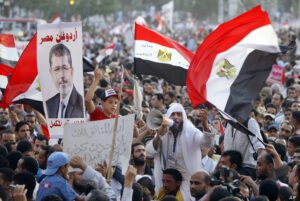

The uprising ended the rule of the regime of Muslim Brotherhood President Mohamed Morsi only after one year in power. It also changed this country’s political course, both internally and at the level of its foreign relations in ways that will have their effect on Egypt’s political future for many decades to come.

“The revolution freed the Islamic religion from those who wanted to hijack it and use it to serve their own political interests and ideologies,” Emad el-Qadi, a former member of the Muslim Brotherhood, said. “The Islamists wanted to establish a fascist religious rule in Egypt, but the revolution put this to an end,” he wrote on Facebook.

Islamists’ rise and fall

The revolution started as a show of anger against Morsi’s failure to put an end to social and economic problems in Egypt during his one year in office.

Those who took to the streets to protest against the Muslim Brotherhood president were also angry at the desire of his movement and party to control all aspects of Egyptians’ life and radicalise the people, enlisting support from the Salafists and other radical Islamist movements, including Jamaa Islamiya which was responsible for the assassination of President Anwar Sadat in October 1981.

Soon, however, the protests morphed into a fully-fledged uprising for the salvation of Egypt.

The same event broke, and probably for good, the nation’s Islamists forces which saw their political heyday following the downfall of Mubarak’s autocracy.

In his three decades in power, Mubarak had given the Islamists little chance to appear on the political stage, even as he allowed the Muslim Brotherhood a marginal presence. He also allowed the Islamist movement to pursue a wide range of social and charitable activities that later proved to have won it support from large swaths of the public, especially the rural poor.

Mubarak’s downfall in February 2011 gave the chance to the Islamist to emerge as a new power on the political stage. This has had resounding, far-reaching effects on Egyptian society and the political order in this populous political country.

The nation’s secular parties became under threat of shrivelling up and extinction because of the Islamists’ domination of the political stage and also because they failed to make their presence felt on the streets.

The Islamists were aware that the political opportunities offered them by Mubarak’s downfall were rare, which was why they did their best to control the political stage and ensure their continued presence by working to change the election laws in ways that only serve their own interests. Morsi also tried to exempt his decisions of judiciary oversight, a move that backfired and proved fatal to his regime.

Apart from ending the domination of the Islamists over the internal political stage, the June 30 Revolution also sounded the death knell for political Islam in the country, especially after the public realised the falseness of the Islamist ideology, which was manifest in the violent reaction to the revolution by the Muslim Brotherhood and its allied militias and parties.

“The Muslim Brotherhood did not have a real political or economic project,” Jordanian political analyst Amer el-Sabayla said. “They posed real dangers, not only to Egypt, but to the whole world,” a local newspaper quoted him as saying.

Change of course

The downfall of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and the collapse of what came to be known as the “Islamist political project” sent the same project tumbling everywhere in the region.

The series of public protest that swept through the Arab region and came to be known as the Arab Spring were manna from heaven for Islamists in the region. The same Islamists rose to the political stage in the Arab region, especially in North Africa, for the first time in decades.

Nevertheless, the Brotherhood’s downfall in Egypt started a chain reaction, causing other branches of the same Islamist movement to sustain one political loss after another.

The Egyptians’ ability to get rid of the Muslim Brotherhood rule also has had deep effects on Egypt’s foreign policy.

The Muslim Brotherhood enjoyed strong links with Iran’s mullahs even before the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran.

When it came to power in Egypt in mid-2012, the Brotherhood made these relations public. Tehran was the second world capital Morsi visited in August 2012, two months after he came to the office of president in Egypt.

Warm relations between the Brotherhood in Iran marked an extreme policy shift for Egypt, one overlooking cultural, ideological and religious rivalries between the two countries, observers said at the time.

Infatuated with the Turkish model, the Brotherhood also nurtured strong relations with Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Turkey which was and continues to be bent on reviving the Ottoman Empire at Egypt’s cultural, political, economic, historical and geostrategic cost.

This policy sent shockwaves to Egypt’s traditional allies, including in the Arab Peninsula where rulers and ruled were gnashing their teeth in anger at the foreign policy shifts taking place in Egypt.

“This is why we say the June 30 Revolution did not only rescue Egypt, but also the whole Middle East region, including the Gulf region,” Kuwaiti political analyst Fouad el-Hashem said.

The post-Brotherhood authorities had to reverse all these internal and external failures.

However, their effect continues to be present now, even eight years after the downfall of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, which makes the mission even more difficult for the current administration in Egypt, observers say.

Discussion about this post