Napoleon once said that every French soldier carries a marshal’s baton in his knapsack. Similarly, a librarian or an office clerk has a slim vanity–published volume of poems hidden in a drawer somewhere like an embarrassment. Blame Oscar Wilde, William Wordsworth and William Topaze McGonigle for making poets look ridiculous, nay frivolous, in the West. Poetry readings on BBC Radio 3 perpetuate the derision.

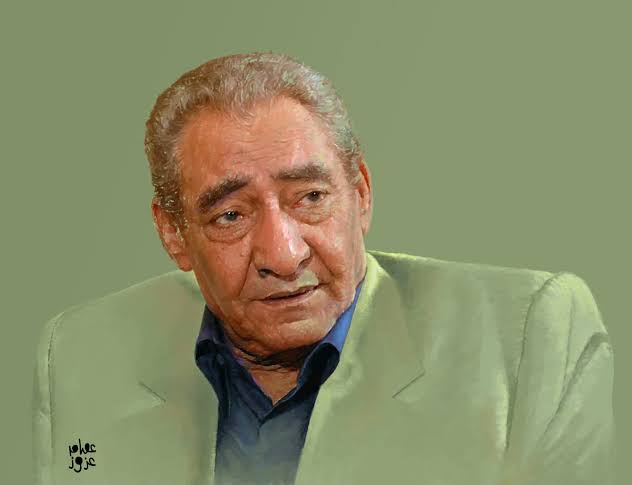

Not so the poetic tradition in the Arab world. The television programme Amsiya Thaqafiyya (Cultural Soirées) featured poetry that adheres to poetic normsmore than one thousand years old. In fact, some poets are seen as a threat to the establishment and suffer behind bars and in self-imposed exile for their politics, as did Abdel Rahman el-Abnudi (1938-2015).

El-Abnudi belonged to a generation of poets who preferred to write in Egyptian dialect, not Modern Standard Arabic, the formal idiom. Unlike the Cockney English of Barrack Room Ballads by the British poet Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), which was pseudo-realism peddled by the upper-classes, el-Abnudi’s use of ammiyya was associated with a “militant political engagement” as he and other Egyptian writers of this school aimed to make their literary output the voice of a political movement towards popular democracy in Egypt.

Born on 11 April 1938, in Qena, Upper Egypt, he was surrounded by books and song from an early age. His father was a cleric and marriage notary, who possesseda rich library. From his mother and aunt, who helped to shape his imagination with the folksongs of Pharaonic and Coptic origins, he learned how to recite poetry inUpper Egyptian dialect.

He later graduated in Arabic language from Cairo University.

His poems commemorated great events in national history, such as the Setback of 1967, the Six Day War, the Camp David treaty with Israel and the January 2011 Uprising.

He wrote lyrics for Abdel-Halim Hafez, Mohamed Rushdie, Najat el-Saghira, Shadia, Sabah and Mohamed Mounir, who were some of the most famous Egyptian and Arab singers in the second half of the twentieth century.

One of his most celebrated poems, Ada el-Nahar (Day has Passed), which he wrote in aftermath of Egypt’s bitter defeat by Israel in 1967, was recorded as a song by Abdel-Halim Hafez and it remains an iconic patriotic song for Egyptians and Arabs.

He was jailed in the 60s during the time of President Gamal Abdel Nasser on charges of being a member of a communist group, but he was released a few days before the Six Day War in 1967. During the Sadat era,he was harassed by the security forces, which made him leave for Tunisia and later, London.

El-Abnoudi published Al-Sirah Al-Hilaliyya, a collection of Upper Egyptian poems. Hisautobiography My Sweet Days was serialised by the daily newspaper Al-Ahram. In 1991 he published his collection of poems, The Arab Colonialism, which formed the first part of a larger anthology in 1994.

Journalist Mohammad Tawfiq produced Al-Khal(Uncle), a collection of stories about el-Abnoudi’s family. (The poet was known as ‘Uncle’) and he was the voice of the poor, the peasants and the working class. Only a critic would dub an artist a spokesman for the downtrodden, and even if el-Abnoudi spoke eloquently about the plight of the parlous proletariat, no one seems to have listened very hard, otherwise their lot might be much improved by now.

While his sideboard may not groan with awards, the Egyptian State Award for Arts took pride of place in 2000, making him the first Egyptian dialect poet to receive the honour. A decade later he received the Nile Award in Arts.

He died on 21 April 2015. He was 76.

Discussion about this post