By Amr Emam

The Nile Museum in Aswan is full of life-size, true-to-reality installations.

One of them is man sitting on the ground and turning on a primitive water pump sparkles with life, even though he is a mere stone statue.

Beside him, an earthenware water jug is placed, as if the man has just finished drinking from it and resumed work on the pump.

The museum, constructed over 11 years and inaugurated only a few years ago, contains examples of real-life items from Nile Basin countries. Its contents mimic everything in these states, including the traditions of the peoples, national dress, agriculture systems, animals and tropical life.

It also manifests Egypt’s new-found cultural, economic and political interest in other African countries, an interest that started to form after revolution that took place in July 2013.

The trip inside the 146,000-square-metre museum is tantamount to one to the ten states of the Nile Basin.

At the entrance to the museum, there is a towering statue of Hapi, the god of Nile flooding in ancient Egypt. The statue leads into an African jungle where full-size statues of animals, including elephants, lions, tigers, crocodiles and hippopotamuses are arranged. Surrounded by large trees, the animals come at the centre for major waterfalls that pour into the middle of the jungle.

A modern sound system creates the feeling of a real jungle, making the sounds of the animals heard to visitors.

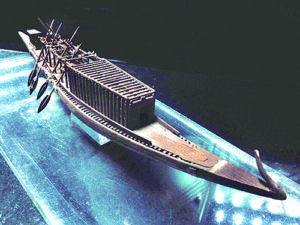

The jungle is only metres from a museum section where a statue of a beautiful woman dressed as a bride sits on the ground. Known in ancient Egyptian culture as ‘Bride of the Nile’, the statue is a representation of a virgin woman thrown into the Nile every year to please Hapi. Tools strongly connected with the Nile in Egypt are scattered around the bride.

This is the museum section tell¬ing the story of Egyptians’ efforts to control the Nile for millennia. It contains testimonies to Egyptians’ interest in this river over the years.

One of these ‘testimonies’ is an ancient water-level measuring tool that dates thousands of years back. The tool was used by ancient Egyptians to measure the level of the Nile flooding to determine the amount of taxes they would collect from farmers who used the flooding in irrigating their farms.

Another tool — a lot more modern — is a light bulb used by Egyptians in the 1960s during the construction of the High Dam, Egypt’s gigantic dam in Aswan, near the border with Sudan. The dam was built to control the Nile flooding and prevent it from destroying farms along the Nile Valley. There is a section inside the museum for every Nile Basin state, exhibiting features of its life and culture. One of the sections contains models of hunting and fishing equipment, including arrows, daggers and trawling nets.

On the walls of the stairs to the second floor of the museum are paintings of scenes from Nile Basin countries. Some of the paintings depict charming landscapes, while others show human activities, such as farming, fishing and irrigation.

On the second floor, there is a massive library that contains thou¬sands of books and maps covering the Nile, the creatures living in it and its geography.

There are also huge aquariums where all types of Nile fish, including the African tiger fish, mudfish, catfish, marbled lungfish and the African knifefish, can be found.

Egypt spent about $10 million to construct the Nile Museum, but the repository is only one aspect of the larger picture of this country’s grow¬ing interest in Africa.

Discussion about this post