Every January 25th, Egypt solemnly observes National Police Day, paying tribute to the extraordinary courage of its policemen who, on that day in 1952, stood defiantly against British forces during the Battle of Ismailia.

Their unyielding resistance in the face of superior firepower became a defining moment, igniting the final push towards national independence and forever reshaping the country’s destiny.

However, Egypt’s devotion to law, order, and justice reaches far beyond the 20th century, stretching across more than four millennia to the banks of the Nile, where one of humanity’s earliest civilizations gave birth to some of the world’s first organized systems of policing.

At the heart of this ancient tradition lay ma’at, the sacred principle of cosmic balance, truth, and justice that Egyptians believed held the universe itself together.

As Dr Ali Abu Deshish, director of the Zahi Hawass Foundation for Antiquities and Heritage and a prominent antiquities expert, explains, preserving ma’at was not merely a legal obligation in ancient Egypt.

It was, he said, a profound religious and philosophical imperative.

This deep commitment to upholding cosmic harmony directly inspired the creation of one of history’s earliest structured police forces: the Medjay.

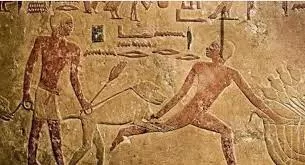

“Originally a nomadic Nubian people renowned for their exceptional tracking skills and combat prowess in the unforgiving Eastern Desert, the Medjay were gradually transformed from outsiders into the very backbone of pharaonic law enforcement,” Dr Abu Deshish told the Egyptian Mail.

In the early periods, policing duties overlapped with military roles. But as Egypt’s territory and influence expanded from the Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC) through its golden age in the New Kingdom (c. 1570–1069 BC), the need for specialization became evident.

The term “Medjay” evolved from an ethnic label into an official title, designating elite desert rangers, border guards, and guardians of royal and sacred interests, from the bustling markets of Thebes to the silent royal tombs of the Valley of the Kings.

Far from rudimentary, the ancient Egyptian police system was remarkably advanced and highly organized.

Oversight was provided by the Chief of the Medjay, who reported directly to the vizier or, in some cases, the pharaoh himself.

Specialized branches handled distinct responsibilities: temple police protected sacred precincts filled with gold and ritual treasures, river police patrolled the Nile, preventing smuggling along this vital artery of trade, market police ensured fair weights, honest dealings, and order in crowded bazaars, necropolis police vigilantly guarded royal burial sites against tomb robbers.

These forces confronted a wide range of offenses, many strikingly familiar today, including assault, adultery, perjury, corruption, and political intrigue.

Crimes, such as tomb robbery and temple desecration were viewed as particularly heinous, not only as theft but as direct assaults on the eternal order of ma’at and the afterlife.

Remarkable evidence of their work survives in the Abbott and Amherst Papyri, New Kingdom documents that record large-scale investigations into tomb robberies in the Theban Necropolis.

These texts reveal widespread corruption, rival inspectors, interrogations, meticulous record-keeping, and severe punishments, reading like true ancient detective stories.

Justice in ancient Egypt aimed above all to restore balance. Lesser offenses might result in public shaming or corporal punishment (sometimes up to 100 lashes), while grave crimes, such as murder or high treason could lead to forced labour, execution, or mutilation, always with the ultimate goal of cleansing disorder and safeguarding societal harmony.

Ancient officers were meticulous innovators, routinely accompanied by scribes who documented every encounter, an early form of evidence-based procedure.

They even employed specially trained police dogs and, in some cases, baboons, whose sharp senses assisted in tracking fugitives and apprehending suspects.

Every officer carried the shuma, a staff that served as both a symbol of authority and a reminder of their sacred duty to protect ma’at.

“They patrolled temples like Karnak, lively marketplaces, and remote desert borders, remaining ever vigilant against any threat to peace and cosmic order,” Dr Abu Deshish said.