The Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) dazzles with Tutankhamun’s golden mask and colossal statues, yet its quietest wonders lie hidden in four intimate “caves”.

Tucked away from the spotlight, these dimly lit chambers abandon grandeur for something far more powerful: the private, human moments of ancient Egypt that history almost forgot.

The Egyptian Mail invites you to step past the golden mask and towering colossi into the GEM’s four hidden “caves”.

Priestess of Hathor Cave

Begin with the hushed sanctuary of the Priestess of Hathor, then wander into the sun-baked streets of Deir el-Medina, two extraordinary galleries that trade pharaonic spectacle for the raw, intimate pulse of real lives lived thousands of years ago.

Here, ancient Egypt stops whispering from pedestals and starts speaking directly to you.

Before you realise it, an unseen current guides your steps past Hall 5 to a low, softly lit doorway. The moment you cross the threshold, the museum’s clamour falls away, the air grows cooler, heavier, almost humming with reverence.

Ochre walls close gently around you. There, glowing beneath a single shaft of light, an ancient hymn unfurls across the wall.

“Holy music for Hathor, music a million times, because she loves music. I am the one who makes the singer sing the morning song to wake Hathor, every day at any hour she wishes. May her heart be at peace with the music.”

And so you step fully into Hathor’s embrace, goddess of music, dance, drunken joy, and fierce maternal love.

In ancient temples her priestesses (often princesses or queens themselves) shook sistra until the air rang like silver bells, their voices rising in hymns that promised rebirth beyond death.

Here, in the half-light, that world feels startlingly close.

Then your gaze locks onto her: the Outer Coffin of Amunet, a breath-taking apparition sheathed in electrum, silver, and bronze that catches the dim glow like moonlight on water.

Across its emerald-tinted surface, proud inscriptions proclaim her as ‘Sole Royal Ornament’.

Amunet’s burial is a love letter carved in cedar. The wood itself was a treasure (fragrant Lebanese cedar, carried across deserts and seas at staggering cost) then painted a celestial blue to mimic the heavens she would soon join.

And there she is (Amunet herself). Not behind glass, not reconstructed, but present. Her linen-wrapped body lies as it was laid centuries ago, still wearing the jewellery that once chimed softly when she danced for the goddess.

Her fingers wear delicate silver rings that once flashed as she raised the sistrum. Around her waist, broad beaded belts of carnelian, jasper, and turquoise lie exactly where loving hands placed them thousands of years ago, vibrant sentinels to guard her forever through the dark.

Most moving of all is her hair, still there. Dozens of tight, perfect braids spill across the linen, their ends artfully curled exactly as she wore them in life.

Here, the truth lands softly but unmistakably: this was a real woman. She once felt the sun on her shoulders, heard sistra clash and laughter rise through temple columns, watched her own reflection ripple across polished bronze as she danced before the goddess.

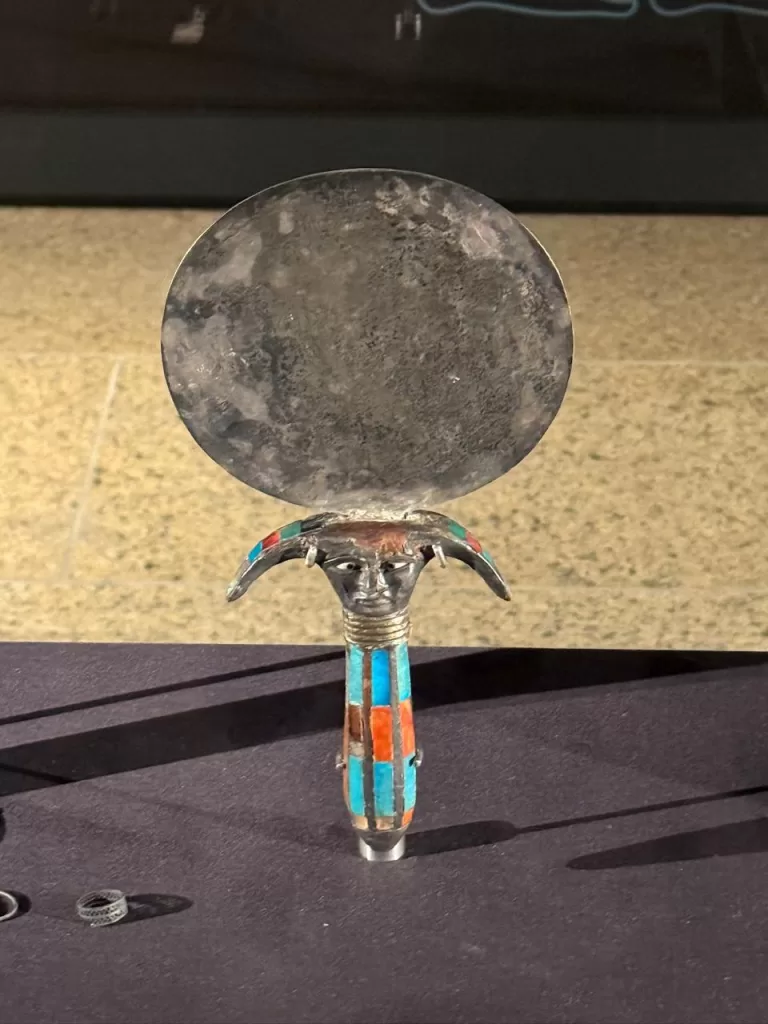

Priestesses of Hathor cherished their polished bronze mirrors, often engraved with tender poems or sacred titles.

In ritual dances, they lifted them high, catching the sun and flinging golden shards of light across the temple walls, an offering that turned every movement into prayer.

The mirror became a perfect circle of radiance, linking goddess to woman, eternity to the fleeting moment.

Nearby, delicate paddle dolls and faience figurines stand in quiet clusters, their tattoo-like markings shimmering with mystery.

These miniature women mirror the living priestesses, embodying the joy, dignity, and resilience of those who served Hathor.

Their sacred task was to channel gentleness and beauty into the world, offering solace and protection, especially to women.

In Hathor’s cave, the line between temple and home dissolves. Small clay fertility figures, tenderly pinched by ancient fingers, sit beside others carved from carnelian or limestone, each one a private prayer once placed on a household shrine.

They speak of hands that reached out, then as now, for love, healing, and hope.

Deir el-Medina Cave

Just near Hall 7, another shadowed doorway beckons. Step inside, and the golden roar of pharaohs falls silent. Here lies Deir el-Medina, the lost village of the artisans.

Far from the royal splendour that fills the museum’s grand halls, this cavern reveals the beating heart of ancient Egypt: the craftsmen, their wives, their children – the ordinary, brilliant hands that carved eternity into stone for the kings.

Deir el-Medina was a walled world unto itself: just 68 mud-brick houses pressed shoulder-to-shoulder, alive with neighbours, quarrels, love stories, and laughter.

At the heart of the cavern stands a scale model of the village, tight clusters of small homes, sunlit courtyards no bigger than a prayer rug, narrow streets where children once chased chickens and artisans argued over beer.

Each house offered three modest rooms, their ceilings kissed by shafts of light from high, deliberate openings.

On hot nights, the flat rooftops became beds beneath the stars, places to sleep, dream, and watch the same constellations that still guard the Valley of the Kings.

While the men vanished at dawn into the Valley of the Kings, women, elders, and children kept Deirel-Medina alive.

Life moved in quiet inheritance: girls at their mothers’ sides learning to grind grain, weave linen, and brew beer, boys trailing fathers, absorbing the tilt of a chisel or the curve of a hieroglyph before they could fully read.

Some boys did learn letters early, copying proverbs and stories on broken pottery or limestone flakes.

Those school exercises still exist, each scrap bearing the unmistakable personality of a child and the patient corrections of a teacher who once stood exactly where we stand now.

This cavern brims not with gold but with the quiet weight of lived days: coarse pottery, flat bread moulds, heavy water jars, shards of painted bowls, small incense burners that still carry a ghost of ancient scents.

Most astonishing are the hundreds of ostraca – limestone flakes and broken pottery covered in hurried ink: shopping lists: love poems and festival plans.

Each scrap is a breath from a real evening, laughter around a shared bowl, gossip in the moonlight, the small triumphs and heartaches of people who never imagined we would read their notes and feel suddenly, achingly at home.

One ostracon, larger than the rest, stops every visitor cold. Scrawled across the pale limestone is a delivery note from a festival long ago: thirty-six villagers pooling their offerings (loaves of bread, clusters of grapes, dried fish, and honeyed cakes), then, beneath the list, a proud postscript: “Additional provisions sent by the vizier himself”.

For one bright evening the entire village set down chisels and worries, spread mats under the stars, and ate together as equals beneath the same sky that once watched pharaohs rise and fall.

Valley of the Kings Cave

You cross an unassuming threshold near Hall 9 and the world changes. The lights dim, the air cools, and the faint echo of footsteps on stone replaces the museum’s usual hum.

You have stepped into the Valley of the Kings as the New Kingdom pharaohs knew it, a narrow, shadowy gorge hiding the most sacred real estate on earth.

This is not a replica tomb, but the necropolis itself reborn. Low amber lighting picks out limestone walls painted with the vivid scenes that once guided kings to eternity.

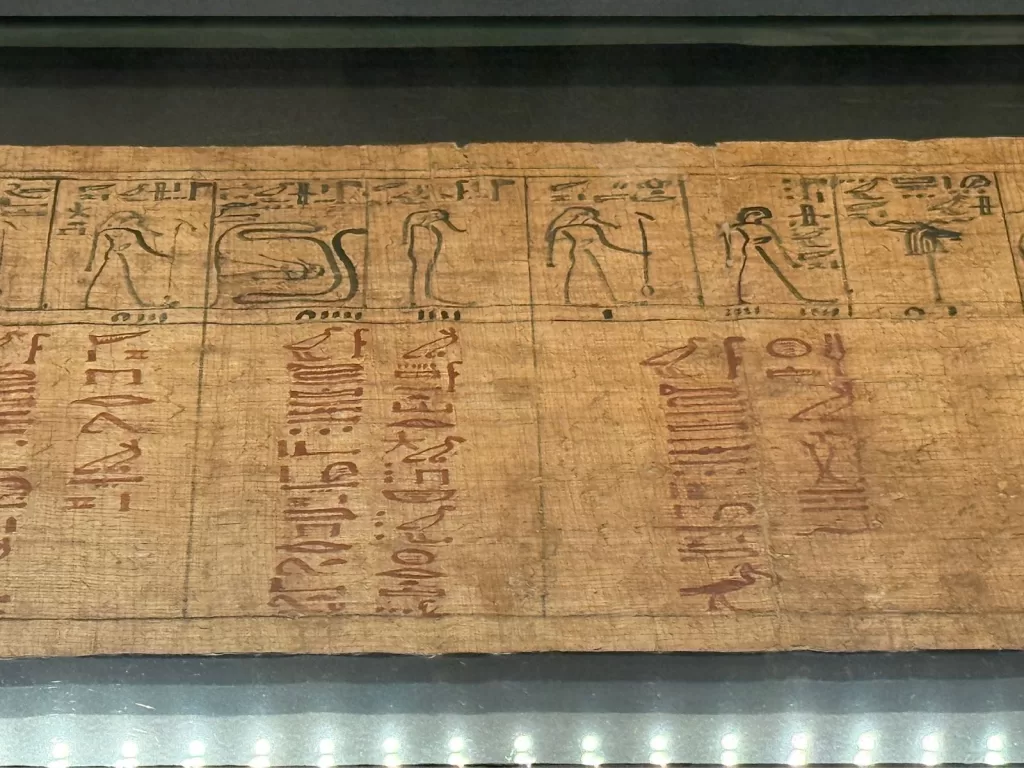

Digital projections breathe life into the ancient texts that cover every surface. The Amduat, the royal funerary book found on tomb walls, unfolds hour by hour across the walls, showing the sun god Ra in his night-barque battling the serpent Apophis while the dead king rides beside him.

Each of the 12 hours is a chapter, each chapter a step closer to the radiant rebirth at dawn. Close by, the Book of Gates dramatises the same journey as a series of guarded portals. At every gate, the sun god must speak the correct name or be devoured.

The king, merged with the god, passes safely because his tomb walls have become the gates themselves. The message is clear: the tomb is not a grave, but a machine for resurrection.

Another wall glows with the Litany of Re – seventy-five names and forms of the sun god, chanted by priests to ensure cosmic order.

Even the famous Book of the Dead, more usually associated with private individuals, appears here in royal versions tailored for pharaohs.

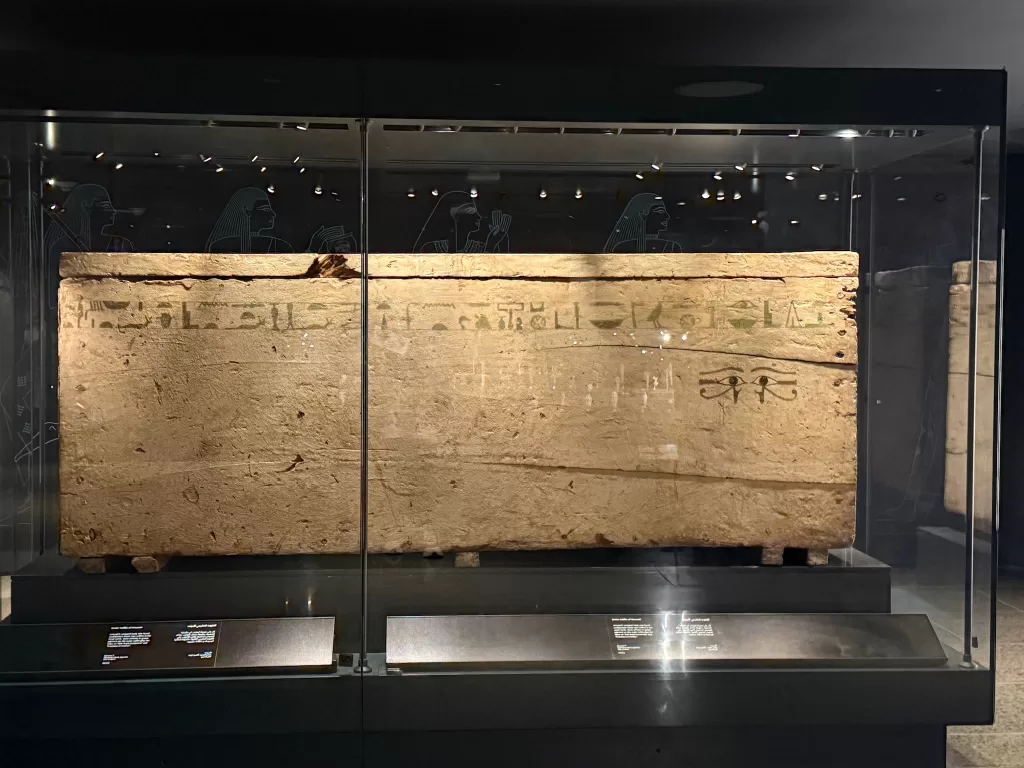

At the centre of the cave, under soft spotlights, lies one of the rarest documents in existence: the Book of Twelve Caves papyrus. Discovered inside a shabti figure of Amenhotep II (18th Dynasty), it is the only known royal funerary papyrus ever placed in a king’s own burial and the earliest version of its text.

Unrolled in a climate-controlled vitrine, its columns describe 12 subterranean caverns, each governed by serpent deities and protective gods who reward or punish the souls of the dead.

The cave does not stop at texts. Reconstructions and original fragments tell the human stories behind the theology.

KV20, probably the first tomb cut into the Valley for Thutmose I, had to be lined with painted limestone blocks because the natural shale crumbled under the chisel.

Some of those blocks are represented here as exact models.

The tomb of Thutmose III (KV34) appears in miniature, its oval burial chamber still startling after 3,400 years.

From Horemheb’s spectacular KV57 come fragments of his canopic chest and tiny embalming tables, reminders that even the grandest tombs were repeatedly robbed in antiquity.

Most visitors pause longest in front of a simple linen shroud. Once wrapped around the mummy of Thutmose III, it is painted with a starry sky and inscribed with protective spells from the Book of the Dead and the Litany of Re.

Four small wooden model oars lie beside it, placed there in Dynasty 21 when high priests rewrapped and reburied the royal mummies in the famous Royal Cache (TT320) to protect them from thieves. Those oars, no longer than a hand span, still carry the weight of eternity.

Sunken Cities Cave

Leave the desert darkness and walk towards the vicinity of Hall 12. The floor beneath your feet becomes a giant map of the ancient coastline from Alexandria to Abuqir Bay.

You have entered the domain of water. For centuries the great port cities of Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus, gateways between the Nile and the Mediterranean, lay forgotten under metres of silt and sea. Then, beginning in 2000, French underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio and the IEASM began raising their drowned splendours.

The GEM’s Sunken Cities cave is the first place on earth where the full drama of that discovery is permanently displayed.

Stone anchors litter the entrance like the bones of ancient ships. Some are pierced with three holes, a design unique to the Late Period and Ptolemaic era, while lead fishing weights, bronze nails, and scattered pottery speak of daily life abruptly ended by earthquake and liquefaction.

Coins bearing the faces of the Ptolemies glint under subtle lighting, dropped by merchants who never imagined their loose change would survive two millennia.

Two colossal red-granite statues dominate the space: representations of King Seti II (19th Dynasty) recovered from the great temple of Thonis-Heracleion. Their inscribed back pillars leave no doubt of their identity.

Rows of sphinxes, some still bearing traces of marine encrustation, recreate the sacred avenues that once led pilgrims to the sanctuaries of Amun-Gereb and Heracles.

A superb marble statue of Aphrodite, fished from the Roman seaside resort of Marina al-Alamain, stands serene at the heart of the gallery.

Mistress of love and protector of seafarers, she once watched over harbours across the Graeco-Roman world.

Along the walls, digital screens project ghostly overlays of what now lies beneath the waves: entire districts of ancient Alexandria, palaces, temples, and the massive foundation blocks of the Pharos Lighthouse, one of the Seven Wonders, still sitting on the seabed where they fell.

Egypt’s past is no longer locked behind glass. In the GEM it breathes, moves, and, for the first time in thousands of years, welcomes visitors home.