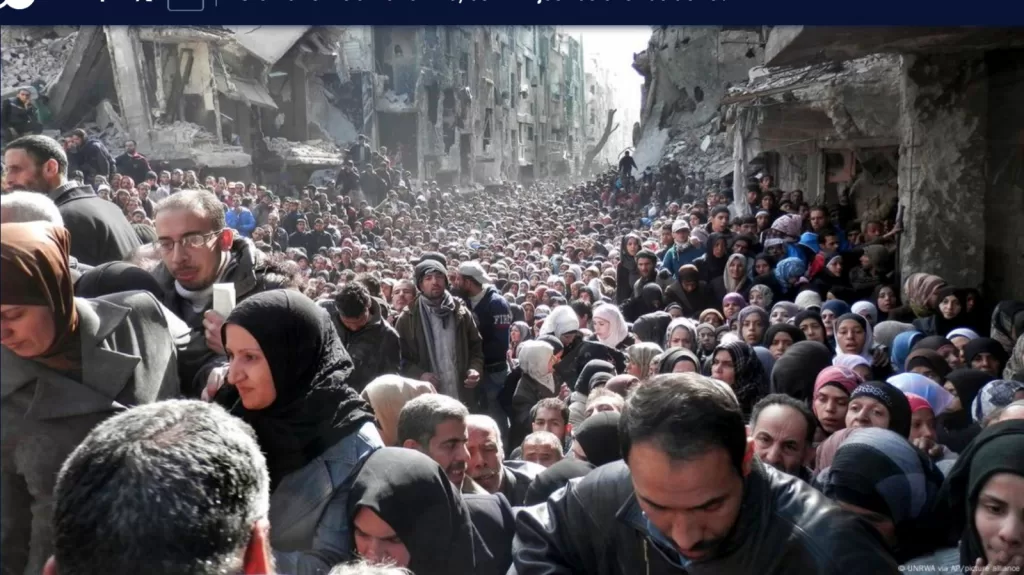

Gaza, Aleppo, El Fasher: Where starvation is a strategy

An ancient war tactic, with today’s victims left in plain sight

Analysis by Mohamed Fahmy

The deliberate manipulation of food supplies has long been recognised in international law as a grave breach of humanitarian principles.

Codified under the Geneva Conventions and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC), the use of starvation as a method of warfare is explicitly prohibited.

Yet in conflicts from Sudan to Syria and, most starkly today, in Gaza, this ancient and brutal tactic is being revived, raising urgent calls for legal accountability.

Human rights experts and international organisations are increasingly framing starvation not simply as a humanitarian tragedy, but as a prosecutable war crime.

“Israel is starving Gaza. It’s a genocide. It’s a crime against humanity. It’s a war crime,” declared Michael Fakhri, UN special rapporteur on the Right to Food, in an interview last week.

His assessment echoes findings by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and UN agencies that Israel’s blockade and restrictions on aid flows are systematically depriving Gaza’s population of food, clean water, and medicine.

This shift in narrative from humanitarian crisis to criminal act is significant. For decades, famine was viewed primarily as a by-product of environmental hardship or governance failure. But as Professor Alex de Waal of Tufts University notes, the recent rise in conflict-driven famines reflects a calculated strategy: hunger being “weaponised” for political and military objectives. This is not collateral damage. It is, in many cases, intentional.

Legal momentum is also building. In 2018, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 2417, explicitly condemning the starvation of civilians as a method of warfare.

In 2019, amendments to the Rome Statute extended this prohibition to non-international conflicts. Most notably, in November 2024, the ICC issued arrest warrants for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and former Defence Minister Yoav Gallant, marking the first time starvation has been charged as a stand-alone crime in an international case.

Yet legal enforcement remains challenging. Proving intent, whether direct or indirect, requires clear evidence that starvation was not merely foreseeable but deliberately pursued.

The absence of precedent means prosecutors face uncharted territory. Still, experts like Rebecca Bakos Blumenthal of Global Rights Compliance see the Gaza case as a potential watershed moment.

While legal debates continue in The Hague and beyond, the humanitarian urgency in Gaza is undeniable and Egypt has been at the forefront of the relief effort.

Since the outbreak of the crisis on 21 October 2023, Cairo has facilitated more than 70% of all aid entering Gaza.

The Egyptian Armed Forces, working alongside the Palestinian Red Crescent, UNRWA, and multiple international partners, have overseen the delivery of over 500,000 tonnes of food, medicine, and fuel.

These efforts have persisted, despite Israel’s destruction of the Palestinian side of the Rafah crossing in May 2024, which severed the primary overland lifeline.

Egypt responded with alternative measures, including airdrops, fuel convoys through Karam Abu Salem crossing, and the medical evacuation of over 18,500 injured Palestinians for treatment in Egyptian hospitals.

The scale of Cairo’s commitment is formidable: 368,000 tonnes of Egyptian aid supplemented by 132,000 tonnes from other countries. Around 209 ambulances and 31,380 tonnes of fuel were supplied. About 168 airdrops, delivering 3,730 tonnes of aid directly to the strip, were conducted.

Yet the logistical and political obstacles are mounting. Over 5,000 aid trucks remain stalled in Egypt due to Israeli closures, alongside 25 airdrops’ worth of supplies awaiting clearance.

Each delay deepens Gaza’s humanitarian catastrophe and strengthens the case that starvation is being wielded as a calculated tool of war.

For Egypt, the stakes are more than humanitarian. As the traditional mediator in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and a key voice in the Arab world, Cairo’s sustained aid effort underscores both its moral stance and its strategic role in safeguarding regional stability.

The coming months may determine whether the deliberate starvation of civilians will finally be prosecuted as the war crime it is or remains a weapon used with impunity.

For Gaza’s population, however, the legal verdict will come too late unless the siege is lifted and food flows are restored now.

Egypt’s actions demonstrate that, even in the shadow of political deadlock, decisive humanitarian leadership is still possible.