He who offers food to others will always find food in every house he enters.

So wrote the author of the Insinger Papyrus, which contains wise sayings and teachings. But was the generous man to dish out for his fellows?

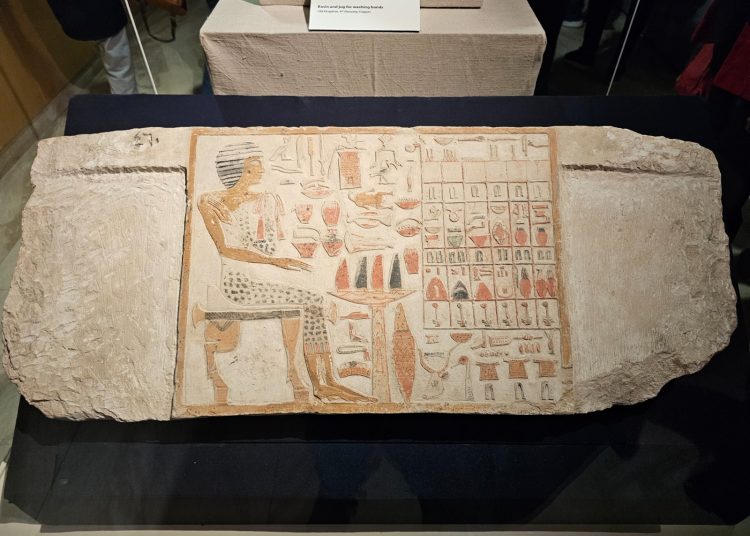

Indeed, ancient Egyptian papyruses that have come down to us cover everything from mathematics to medicine, from science to religious ritual. But no cookbook — nothing even resembling a recipe. What we do know about ancient Egyptian foodies has been gleaned from tomb paintings. Baking bread and tasty tiger nut treats are clearly illustrated in soft hues of brown, red and yellow. We also have an idea about how the ancients prepared and served their food judging from the utensils found in tombs.

Such objects are on display at a temporary exhibition, ‘On Tablia’ at the in the Egyptian Textile Hall of the National Museum of Egyptian Civilisation (NMEC) in Fustat.

For the ancient Egyptians, the deceased still needed to eat in the Afterlife. They were accompanied on their journey with comestibles similar to those which they would have consumed in this world. Food symbolised the connection between mortals and the divine. Food offerings would deserve favour from the gods, as was the case in the ancient civilisations of Greece and Rome.

Among the exhibits at the NMEC are a grilled goose and a leg of lamb dating back to New Kingdom (1550-1069 BC), which look far from appetising. As for the dishes made with doum (an oval-shaped fruit from the palm tree), dates and dried raisins, they are thousands of years past their ‘best-by’ date. The ancients most probably partook of lamb, venison, rabbit, duck, goose and pigeon (all grilled), as well as sea fish and freshwater varieties — tilapia, perch, sea bass and mullet.

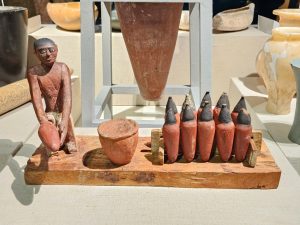

Furniture and utensils on display include a 5,000-year old alabaster offering table from the 12th Dynasty King Amenemhat III (1878-1840 BC), a set of serving dishes in quartz and alabaster for food and fruit from the 1st Dynasty (3100 – 2890 BC) and an Old Kingdom (2700-2200 BC) copper ewer and jug for washing hands. Dating from the New Kingdom is a fire lighter, which consists of a wooden block with holes to contain resin and a stick to create the spark by friction. A pottery oven from the Byzantine era, an okra faience-made model of the 18th Dynasty (1550- 1295 BC), and a wooden Mefrak (Cooking Tool) dating back to Roman era are also on display.

With the advent of Islam to Egypt came recipes of fried meats accompanied by rice. During the Fatimid and Mamluk periods the culinary repertoire was extended with several varieties of yamish, nuts and dried fruits.

Numerous kinds of sweets and baked items sweetened with sugar such as kunafa, qatayef and sambusak were added to the list of mediaeval Egyptian delicacies.

The display includes an Ottoman Era brass mortar with two small handles in the shape of a lion’s head, a Mamluk-era brass food container consisting of three pans and a lid and a brass Mamluk vessel with a hinged lid bearing an inscription in Persian calligraphy that reads: “The owner is Abdulaziz bin Muhammad bin Hussein”.

In contrast with the total absence of foodie writing, Abu Muḥammad al-Muẓaffar ibn Naṣr ibn Sayyār al-Warrāq in the 10th century AD compiled the earliest known Arabic cookbook, Kitāb al-Ṭabīkh (The Book of Cooking) describing over 600 recipes.

Another book with the same title was produced by the 13th century author Muhammad bin al-Hasanal-Baghdadi, but the most resounding title is that of the tome by 14th century writer Kamal Al-Din bin Al-Adim Kitab Waṣlah ilá al-ḥabīb fī waṣf al-ṭayyibāt wa-al-ṭīb (A link to the beloved in describing good things and goodness) — not exactly yummy, but full of promise.

The NMEC exhibition runs until 29 February.

Discussion about this post