Egypt was of strategic importance to Byzantium due to its location at the intersection of western Asia, northern Africa, and the Mediterranean Sea.

It was also a religious, intellectual and economic centre of Byzantium for hundreds of years.

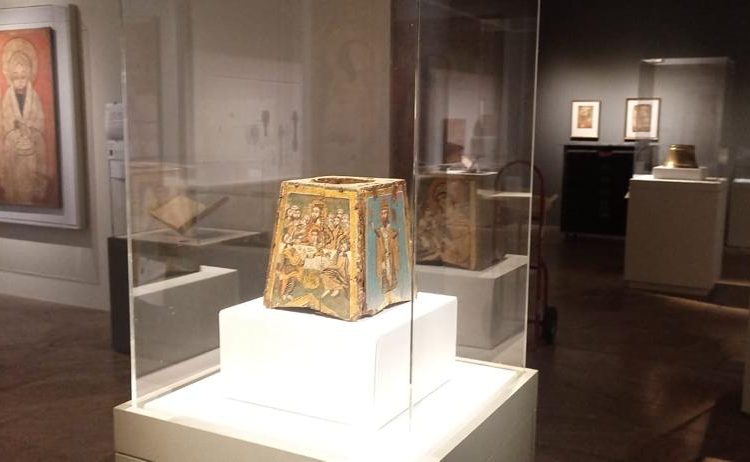

For that reason, Egypt forms part of the Africa & Byzantium exhibition currently at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York until 3 March 2024.

The exhibition will be at the Cleveland Museum of Art in Ohio from 14 April 2024 until 21 July 2024.

Ten countries including Italy, England, Tunisia, Sudan, and Germany are also taking part in the exhibition, which sheds new light on the staggering artistic achievements of mediaeval Africa. The artistic contributions of North Africa, Egypt, Nubia, Ethiopia, and other African kingdoms whose pivotal interactions with Byzantium had a lasting impact on the Mediterranean world.

Moamen Osman, head of the Museums Sector at the Supreme Council of Antiquities, said in the opening ceremony last month that Egypt has presented throughout its history a model of co-existence between different cultures and customs.

“Many civilisations lived in harmony in Egypt and its relations with various countries were influential,” Osman added.

“Egypt also played an important role in the flourishing of relations and cultural exchange with the Byzantine Empire (circa 330-1453),” he said.

The province of Byzantine Egypt was an intellectual, economic, and religious centre where people spoke and read Egyptian, Greek, Latin, Aramaic, and Persian.

The coastal city of Alexandria was a hub of learning and commerce. Its port supplied Egyptian grain to Constantinople, the imperial capital.

Religious debates there led to the development of the cult of the Virgin Mary, and the image of the Virgin and Child spread from Egypt across the Mediterranean basin.

“Byzantine Egyptian jewellery and large-scale textiles incorporated both secular and religious imagery with significant links to the imperial capital and shed light on the lasting impact of the classical Graeco-Roman past. Elite patrons throughout Byzantium commissioned luxury objects made in Egypt as markers of class and status,” the museum website says.

“The exhibition explores Africa’s position within the Byzantine world’s artistic, cultural, economic, and sociopolitical life. From the fourth to the seventh century, early Byzantine visual and intellectual culture was shaped by wealthy patrons, artists, and religious leaders in northern Africa,” it said.

Egypt joined the exhibition with 11 artefacts, which were borrowed from the collections of the Cairo Museum, the Coptic Museum and Saint Catherine’s Monastery.

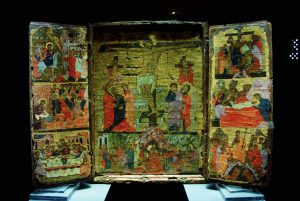

They include the Coptic Museum’s triptych, which features Byzantine style and iconography. This thirteenth- to fifteenth-century triptych depicts the complete events of Holy Week. Painted Icons from Egypt testify to the multiple cultural and intellectual spheres that elites belonged to, as well as the circulation of artworks through trade and political networks.

There is also the Wooden Chalice Case. Painted wooden chalices remain an important feature in the Coptic liturgy. The depiction of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child on the painted chalice represented a revival of Byzantine-era iconography in the mid-eighteenth century when Egyptian artists renewed the art form centuries after it had fallen out of fashion.

Assuming the form of a multi-storied house, a magnificent, ivory-inlaid Bridal Chest is decorated with encaustic paintings, which appear to have a Mediterranean source.

This wood chest has twenty-one inlaid ivory panels, incised and filled with red and green wax paste. The panels depict mythological motifs related to fertility and prosperity. The figures represent the Egyptian god Bes, elegant maenads, and satyrs killing mythological beasts. The wood and metal were likely local materials, and the ivory was procured from trade routes controlled by the Aksumites.

On display also two metal crowns are broad circles of beaten silver, richly encrusted with various gems and adorned with royal and divine insignia, including representations of Horus and Isis.

Also on display is the icon with the Virgin and Child, saints, and angels, which is one of the oldest surviving icons in the world. Mary sits on a bejewelled throne wearing red shoes, attributes of imperial imagery. Holding the infant Jesus on her lap, she is flanked by Saints Theodore and George holding their martyrs’ crosses and wearing military dress. Behind these stiffly formal figures, two angels lean backwards.

Another stunning artefact is the Lampstand of Apollo and other gods representing the luxurious artworks excavated from the tombs of late antique royalty in Ballana and Qustal, cemeteries in Lower Nubia. This late fourth-century/early fifth-century lampstand exemplifies how local artists translated classical art in this later period.

Discussion about this post