LOS ANGELES – Despite the challenges of distance learning during the pandemic, public school systems across the US are setting up virtual academies in growing numbers to accommodate families who feel remote instruction works best for their children.

A majority of the 38 state education departments that responded to an Associated Press survey this summer indicated additional permanent virtual schools and programs will be in place in the coming school year.

Parent demand is driven in some measure by concern about the virus, but also a preference for the flexibility and independence that comes with remote instruction. And school districts are eager to maintain enrollment after seeing students leave for virtual charters, home schooling, private schools and other options — declines that could lead to less funding.

“It is the future,” said Dan Domenech, executive director of the American Association of School Administrators according to AP.

“Some of these states might be denying it now, but soon they will have to get in line because they will see other states doing it and they will see the advantages of it.”

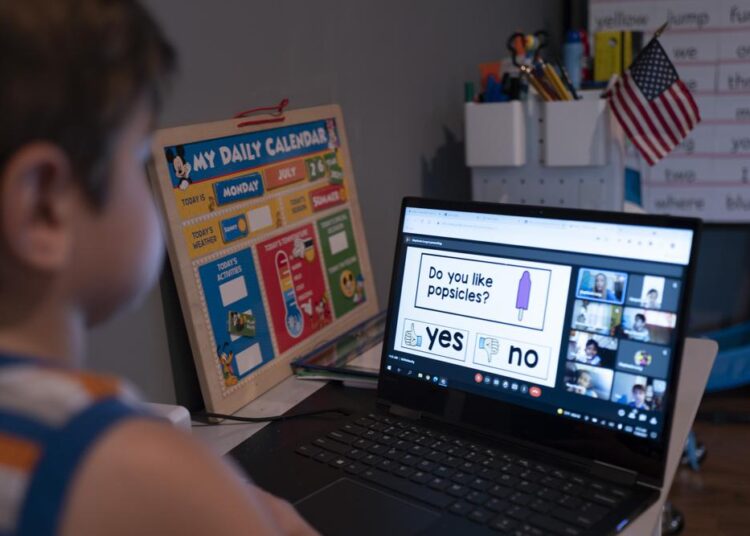

New Jersey parent Karen Strauss lost a brother-in-law to the pandemic. Her vaccinated teenager will return in person but she wants her 5-year-old son at her Bridgewater home until he can get a shot. Strauss said Logan has excelled online under the guidance of his teachers, who will not be available if she home-schools him.

“If learning from home is what’s best for them, why not do that? What’s the reason, except that people are afraid of change?” she said.

School districts’ plans for long-term, full-time virtual programs – which had been rising gradually – spiked during the pandemic. Students in virtual academies generally are educated separately from a district’s other students.

In Virginia, before the pandemic, most of the locally operated virtual programs offered individual courses only to students in grades 6-12, and few, if any, offered full-time instruction.

In the new school year, 110 of the commonwealth’s 132 school divisions will use Virtual Virginia, a state-operated K-12 program, to provide some or all of their full-time virtual instruction, spokesman Charles Pyle said. So far, 7,636 students have enrolled full time for the fall, compared with just 413 in the 2019-20 school year, he said.

Elsewhere, Tennessee state officials approved 29 new online schools for the 2021-22 academic year, which more than doubles the number created over the last decade, spokesperson Brian Blackley said.

Colorado fielded two dozen requests for permanent single district online options along with six requests for permanent multidistrict online schools, according to spokesman Jeremy Meyer, who said numbers are up compared with pre-pandemic years. Minnesota also saw a substantial increase, approving 26 new online providers by July, with 15 applications still pending.

In New Mexico, which like most states is requiring schools to offer in-person learning this year, Rio Rancho Public Schools used federal relief funding to add the fully remote K-5 SpaRRk Academy.

A survey found nearly 600 of the 7,500 student families were interested in continuing virtually, including many who liked being more involved with their children’s education, said Janna Chenault, the elementary school improvement officer.

“We teetered back and forth at what grade to start,” Chenault said, “but we did have interest from some kindergarten parents and we wanted to keep them in our district, so it’ll be K-5.”

Although the spread of the delta variant and rising infection rates have cast a shadow over the start of the school year, President Joe Biden and educators across the country are encouraging a return to in-person instruction, largely because of concerns that many were served poorly by distance learning.

Test scores in Texas showed the percentage of students reading at their grade level slid to the lowest levels since 2017, while math scores plummeted to their lowest point since 2013, with remote learners driving the decline.

Louisiana tests results also showed that public school students who attended in-person classes during the coronavirus pandemic outperformed those who relied on distance learning.

Pre-pandemic research raised questions about the performance of fully virtual schools. A 2019 report from the National Education Policy Center said data was limited by disparate reporting and accountability requirements but showed that of 320 virtual schools with available performance ratings, only 48.5% rated acceptable.

But Domenech said families seeking out virtual school often have children who are strong students and feel held back in classrooms.

“These are the self-starters, students that are already doing very well, probably in terms of the top 10% of their classes, so remote learning is a great opportunity for personalized learning that allows them to move at their own pace,” he said.

Before the pandemic, 691 fully virtual public schools enrolled 293,717 students in the 2019-20 school year, according to National Center for Education Statistics data. That compared with 478 schools with an enrollment of just under 200,000 in 2013-14. Projections for the coming school year are not available, NCES said.

States vary in their approaches to remote learning, with some, like Idaho, leaving decisions entirely to local boards. Others require districts to get state approval to operate their own online school outside any that may exist for students statewide.

Massachusetts requires detailed proposals from districts that must address equitable access, curriculum and documented demand. New Arizona online schools are put on probation until they’ve proven their academic integrity through student performance.

At least some of the virtual schools that districts set up may never take in students. In North Carolina, 52 districts made plans for fully virtual schools, although some were set up as contingency plans in the event they were needed, state education department spokesperson Mary Lee Gibson said.

In states like New Jersey, Texas and Illinois that have removed widespread remote options, restricting them to students with special circumstances, some parents are pushing back.

“We’re not trying to stop anybody from going back to school or the world from trying to come back to some sort of normalcy,” New Jersey mother Deborah Odore said. She wants her son and daughter, who are too young to be vaccinated, to continue remotely this year for health reasons.

“We’re not being given an option,” said Odore, who is part of a parent group petitioning to change that.

Although many parents had a rocky experience with online learning during the pandemic, they often experienced a version that was implemented with little planning. Parents left with a negative impression of distance learning could slow its overall growth, said Michael Barbour, who researches online learning at Touro University California.

“Even if that option was available to them three years, five years from now, that sort of experience has tainted it for them,” he said.

Discussion about this post