Let’s get the controversies out of the way first.

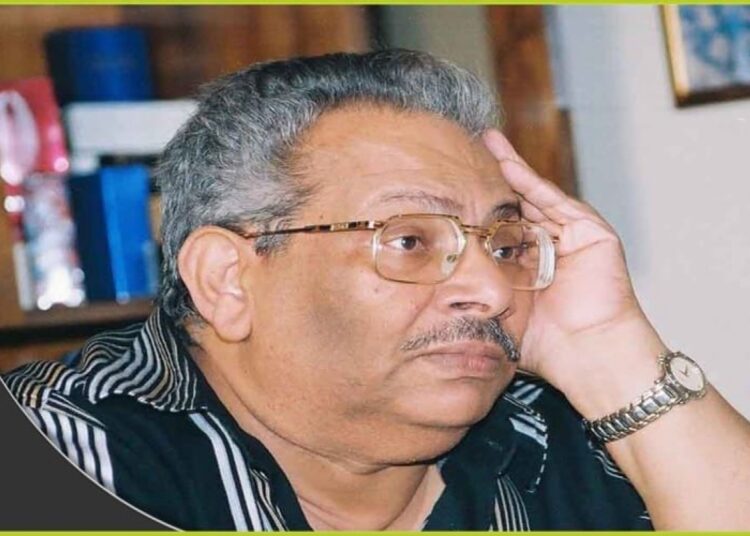

The already famous series writer Osama Anwar Okasha in the 1980s traced the upheavals of recent Egyptian history as experienced by a single family in Al-Shahd wal-Dimou (Sweet and Sour). The other series, Layali Al-Hilmiya (Nights of Al-Hilmiya) was a similar experiment, but dealing with a neighbourhood in Cairo. The Wafdists did not like them. The Muslim Brotherhood, the Nasserists and the supporters of Anwar Sadat were incensed. Okasha was far from repentant. His attitude was on the lines of “the truth hurts”, but he could not separate his writing from politics, otherwise, there would be no depth or value.

If ever there was a flag-waver for Gamal Abdel Nasser, Okasha was waving that flag. Later in life, the flag lay still. Okasha no longer believed in the ideas that Nasser espoused. The Arab League should be dissolved and an economic commonwealth of Arabic-speaking countries should be established, he said.

An ardent secular intellectual, Okasha attacked religious fundamentalism in Egypt. Asked to write a television series on the life of Amr Ibn Al-As, who conquered Egypt in 638 AD, he did his research to draft a script. Then, he changed his mind.

Okasha was born on July 27, 1941, in the Nile Delta town of Tanta. He graduated in sociology from Ain Shams University in 1962. He worked as a government employee until 1981 when he decided to be a full-time writer.

He wrote a weekly column for Al-Ahram daily newspaper.

In the 1960s, Egyptian television drama was unbroken soil. Soap operas like Al-Qahira wal-Nass (Cairo and the People) began to appear. In the late 1970s, more soaps meant that Okasha became a household name. A series by him would draw viewers in their millions, offering rick pickings for the advertisers. However, he fell out with the advertisers because the latter wanted big name actors for the sake of big sales later. Okasha did not want to become a hack, whose work would be interrupted by jingles and bratty kids singing about crisps.

In the mid-2000s, his Canarya wa Shurakah (Canary and his Partners) and Afarit Al-Sayala (The Demons of Al-Sayala) were shown not for the sake of commercials or particular blockbuster actors.

Only during writing and establishing a character, he begins to think of who might play that character. “And one can always change one’s mind later. The serious thinking starts only after the writing process has ended,” he said. There have been exceptions. He began Rihlat Abul-Ela el-Bishri (The Journey of Abul-Ela el-Bishri) and Damir Abla Hikmat (Headmistress Hikmat’s Conscience) to write parts for Mahmoud Morsi and Faten Hamama, but it did not turn out that way.

Okasha’s pet-project, Al-Masrawiya, is an ambitious attempt to show 100 years of social development in a single town, Madinat Al-Markaz — literally, town of the centre — and the handful of villages around it. This is a clear echo of Al-Shahd wal-Dimou and Layali Al-Hilmiya.

He was the first to think of a series that would extend over several years and follow the lives of the same characters. In 2005, he worked on the third instalment of Ziziniya, which is set in the Alexandrian neighbourhood of the same name.

He died on May 28, 2010 after a long battle with illness. He was 69.

Discussion about this post